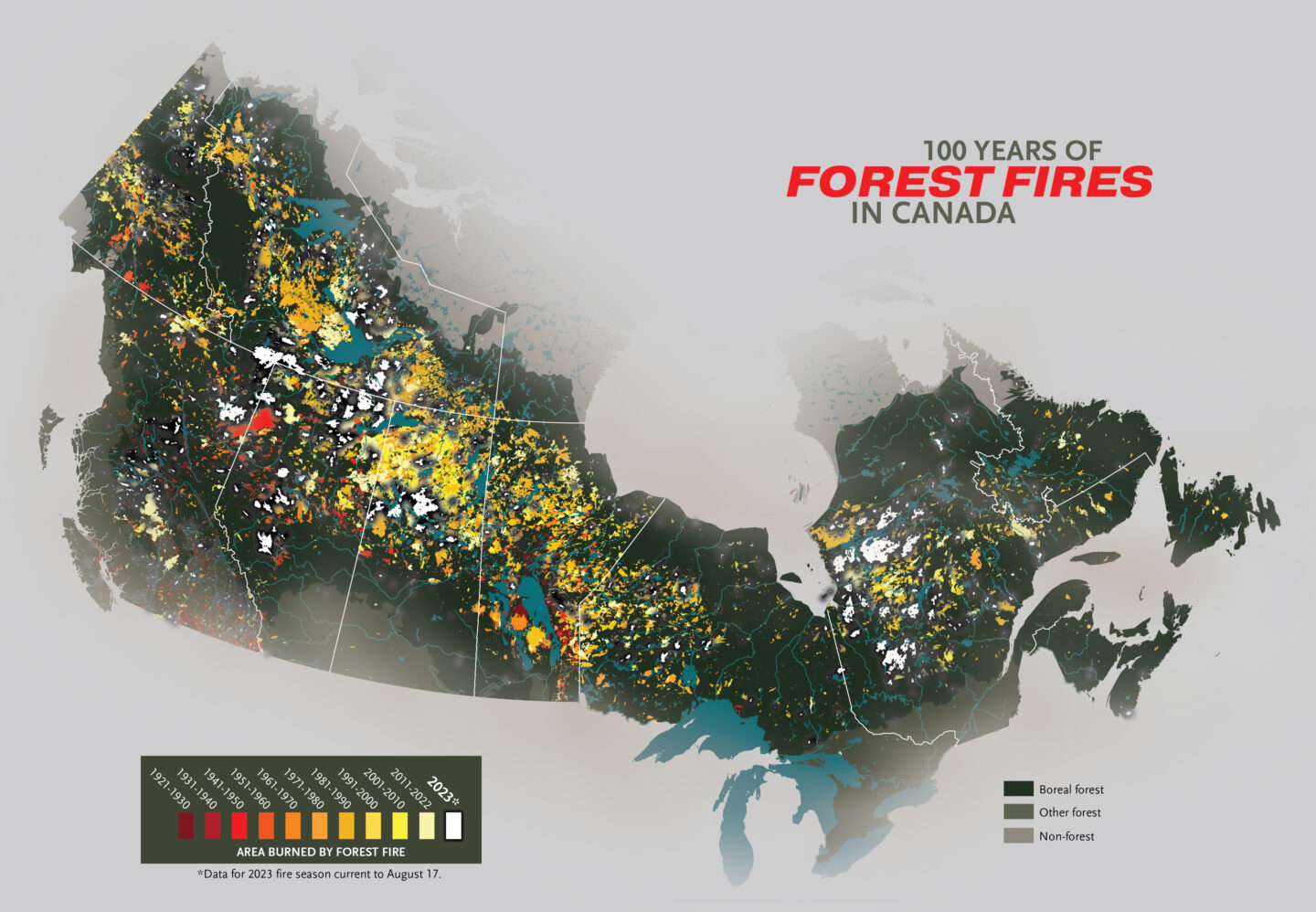

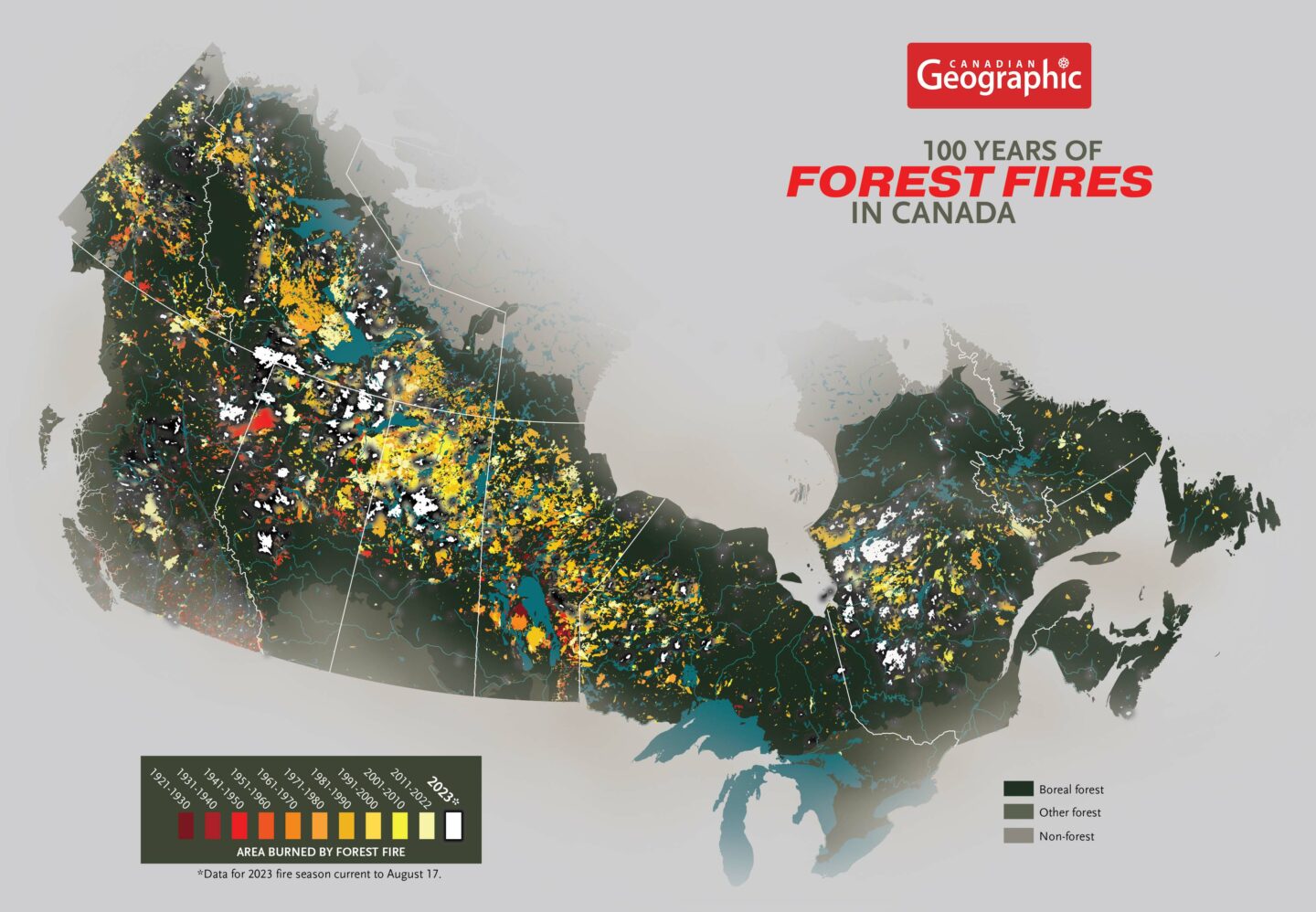

Canadian Geographic cartographer Chris Brackley notes that data from prior to 1975 is incomplete. Since 1975, fire data has been collected via satellite imagery, which gives a complete and relatively consistent picture of fires throughout all of Canada. In the pre-satellite era, fire data was collected provincially/territorially using a variety of methods, from on-the-ground mapping to aerial photo interpretation. In general, this mapping was focused on populated areas, and rarely documented forest fires in the mid and far north. As provincial/territorial priorities changed, there were also varying levels of effort placed on forest fire mapping over time, including periods where no mapping was done at all in a given province.

The province with the most complete record is British Columbia, where the BC Forest Service began compiling a fire atlas on rolled linen base maps in 1919 for fires greater than 50 acres (20 hectares) in size, though even there, areas north of 56 degrees latitude were not well mapped until the 1940s. Says Brackley, “While this map is instructive in seeing the patterns of fire over time, it should be read with the understanding that the older data does not represent the full picture of historical forest fires in Canada.”

Why is Canada’s 2023 fire season so bad?

El Niño, a cyclical warming of the Pacific Ocean that impacts weather patterns on land, is partially to blame for this fire season’s intensity, says Jennifer Baltzer, Wilfrid Laurier University professor and Canada Research Chair in forests and global change. But climate change is the true driver.

“Northern Canada has warmed about four times faster than the planetary average. So now, when we have these El Niño events, because we have a warmer climate, it plays out in the kinds of things we’re seeing this summer.”

Record-breaking years are becoming more common as our climate heats, with or without El Niño — 2014, 2017, 2018 and 2021 were all big fire years in Western Canada. The flames are mostly fed by the mighty swaths of boreal forest, which has burned and regenerated cyclically for millennia. Fire is part of what keeps the forest healthy. But the boreal is now burning deeper and in shorter intervals. Baltzer’s research has found that spruce forest (the dominant boreal species for thousands of years) that has experienced deep, short-interval burning is increasingly not regenerating, replaced instead by shrub thickets and grassland. “It suggests that we’ve reached some kind of threshold in this forest system,” says Baltzer. “This is important when we think about the parts of the landscape that store the most carbon and support important species, like caribou: those are spruce forests.”

Now, as fire continues to claim hectares on hectares, the question remains just how extraordinary the 2023 fire season will prove to be — and what it signals for future fire seasons in the Anthropocene.