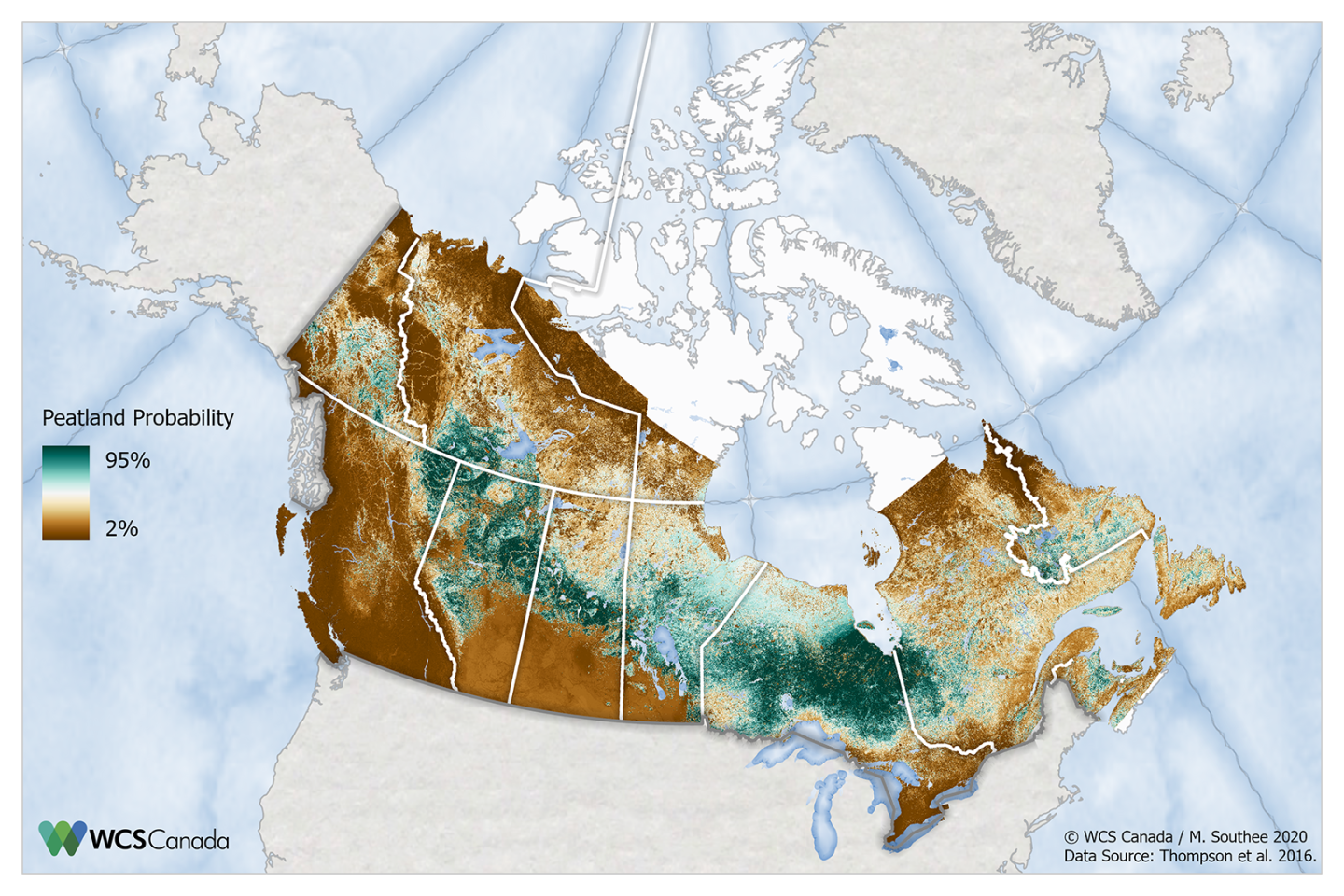

Peatland probability across Canada. (Map: Meg Southee/WCS Canada)

What’s clearer is the impact of human development on peatlands. When mining projects or other developments lead to the draining of peatlands, the peat dries out and becomes more susceptible to fire, which can release huge amounts of greenhouse gases. These fires can linger, smoldering below the surface for years before emerging again as permafrost thaws.

When peatlands are flooded to create hydroelectric reservoirs, meanwhile, carbon dioxide and the even more powerful greenhouse gas, methane, are released. Currently, the Hudson Bay Lowlands contain some of the last mighty undammed rivers of North America, which transport large quantities of nutrients and organic material to the coast and make the bay’s coastal zone very biodiverse.

These lowlands are home to a great variety of life, including many nationally and globally rare plants and lichens. Species of national conservation concern found here include caribou, wolverines, polar bears, lake sturgeon, red knots and Hudsonian godwits.

The draining or drying out peatlands doesn’t just impact the climate; it also affects the rich abundance of species that rely on these areas. In fact, peatlands play an important role in biodiversity conservation, protection of species at risk, water storage and water purification, and in maintaining air quality.

Peatlands are also part of the traditional territories of many Indigenous Peoples across Canada who remain deeply connected to these places as a basis for their social, community, cultural, and economic values. In fact, First Nations are often playing a central role in conserving these places, through monitoring and stewardship as well as through new Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas, while also sharing their deep traditional knowledge with scientists.

We have much to gain from properly caring for peatlands and a lot to lose from poorly planned development. The impact of proposed major mining activities and roads in Ontario’s Ring of Fire on peatlands and their carbon storage, water filtration and wildlife habitat functions, for example, need to be examined before we start building roads or mines.

Simply carrying on with business as usual in these highly sensitive areas could quickly compromise these irreplaceable values and unlock vast amounts of carbon — the last thing our atmosphere needs right now. And as we have seen with the current COVID-19 crisis, disturbing wild areas can have serious unintended consequences. We need to better appreciate how the health of these places is tied to our health.

We really do owe peatlands a little more respect.

Meg Southee is a GIS Analyst and Spatial Data Manager for WCS Canada who has created a number of story maps over the years displaying important maps and associated information for WCS’ work in Ontario in particular.