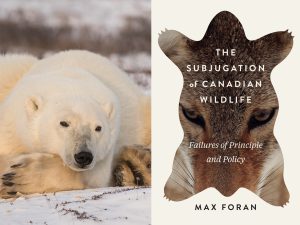

How is the changing Arctic sea ice affecting the well-being of polar bears? That’s just one of many questions Queen’s University biologist Peter van Coeverden de Groot is hoping to answer with some innovative non-invasive research techniques. Inuit hunters — who are often skeptical of more invasive polar bear research methods — are prepared to give de Groot’s methods a chance, and those from the Gjoa Haven Hunters and Trappers Organization in M’Clintock Channel, Nunavut, are working with him to conduct the study.

There are more than a dozen distinct populations of polar bears spread across the Canadian Arctic. Little is known about most of them, apart from Hudson Bay bears, which have been relatively well studied. In the past, surveying polar bears usually meant tranquilizing them from a helicopter, and although this is changing — with less invasive methods such as counting animals from an airplane and taking biopsies using darts — the coverage is still limited to detailed information from a relatively small area over two or three years. “Because most bears are unmonitored at any given time due to the expense, researchers make a lot of inferences based on scarce information,” says de Groot.

The methods de Groot is evaluating with his hunter colleagues use neither aircraft nor biopsy guns. Rather than seeking the bears out, they simply collect and analyze what has been left behind: hair, footprints and feces.

The hunters collect hair samples from snags baited with seal meat and record sex and age by examining tracks. Back in the lab, analysis of hair samples confirms sex and enables genetic identification of individual bears. With enough sampling stations and genetic data from feces, de Groot can estimate the minimum number of bears known to be alive in the area.

“With feces,” says de Groot, “we can track what a bear has been eating — six months ago, three months ago and for its most recent meal. We can postulate as to how stressed the bears are by determining levels of stress hormones. We can postulate as to how healthy they are by identifying gastro-intestinal tract diseases.”

And this non-invasive study has added economic benefits for local Inuit. Since 2001 the polar bear sport hunt has been curtailed in M’Clintock Channel. The hunt provided a much-needed source of income for Inuit hunters working as guides, and no activity has replaced it. De Groot’s research techniques capitalize on the hunters’ knowledge and experience of polar bears and the sea ice, and they’re paid to spend time on the land using this expertise.

De Groot has been working to validate and prove the viability of his new methods, and that phase of the research is nearly finished. He and his Gjoa Haven colleagues are looking forward to seeing this kind of polar bear surveying done in other areas as well.

“We need more complete information on polar bears, and we need alternative ways to get it,” he says. “This is a different way of doing polar bear surveys — and its backbone is hunters on snowmachines. It’s their knowledge and their effort that makes it work.”

This is the latest in a continuing blog series on polar issues and research presented by

Canadian Geographic in partnership with the Canadian Polar Commission. The polar blog will appear online every two weeks, and select blog posts will be featured in upcoming issues. For more information on the Canadian Polar Commission, visit

polarcom.gc.ca.