Environment

Last bastion of ice

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

- 2894 words

- 12 minutes

Environment

Glaciers in the Columbia River Basin are about 38 per cent thicker than we originally thought, according to research published in the fall. A research team from the University of Northern British Columbia measured glacier thickness from 2015 to 2018 using ice-penetrating radar. The team found that the average ice thickness of the glaciers was 92.5 meters, suggesting that previous results underestimated the thickness by 28 to 49 per cent.

Read the study in the Journal of Glaciology

A study published in the Journal of Cryosphere suggests ice is melting 57 per cent faster than in the previous three decades. Altogether, an estimated 28 trillion tonnes of ice have melted away since the mid-1990s.

Melting land ice added enough water to the ocean during this time period to raise the global sea level by 3.5 centimetres on average. Mountain glacier ice loss accounted for 22 per cent of the annual totals of sea level rise.

In Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., the Canadian-based social enterprise Sea-Ice Monitoring And Real Time Information for Coastal Environments has installed sensors near Husky Lakes to monitor ice thickness. For residents, it makes a huge difference — not having to guess ice thickness gives harvesters and travellers more confidence when travelling across the ice.

Similar sensors are set up in Pond Inlet, Nunavut, and Nain and St. John’s in Newfoundland. The information the sensors gather is used to create maps with GO, SLOW and NO-GO zones, along with community-based interest markers like good fishing areas.

The Arizona-based Planetary Science Institute recently published the most detailed map of where future Mars astronauts can find the most crucial resource: water. Recent data has shown there may be ice closer to the equator of the red planet, instead of just in the polar caps — where it would be too cold for astronauts to go, should they get to Mars in the first place.

Why is it important to find usable water — and ice — on Mars anyway? Because the trip will be so long that astronauts will have to grow their own food and create their own fuel in order to return home.

The more water stored in glaciers, the less there is in the oceans — and the lower the sea level is. Until recently, computer models have been unable to reconcile sea level with the thickness of glaciers, so it’s been difficult to determine past glacier melt effects on sea level rise.

A team of researchers and climate experts from the Alfred Wegener Institute have now solved the problem using an analysis of sediments from core samples collected from the seafloor. The sediments contain corals, which can only survive in well-lit waters near the ocean’s surface, indicating that 20,000 years ago the sea level was about 130 metres lower than it is today.

Read the full journal article, published in Nature Communications

Scientists were stunned recently to discover intact plant fossils in a long-forgotten sample of dirt from beneath the mile-deep Greenland ice sheet. The sample was collected in the 1960s by the U.S. army and laid in a drawer, mostly forgotten, in Copenhagen, Denmark for the last few decades.

In 2019, U.S. scientists from the University of Vermont and the University of Buffalo rediscovered the sample and were surprised to see fossilized twigs and leaves, suggesting that the area had been free of ice in the recent geological past — and that a mossy and perhaps shrub-covered landscape once was there instead.

Learn more about the discovery

Harp seal pups are born on the ice — in fact, the species hardly spends any time on land, travelling mostly on ice. They feed in the oceans but return each year to the ice where they were born to give birth. This year, the seals that usually return to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to give birth on the ice around the Îles de la Madeleine in Quebec couldn’t get back — there was no ice.

It’s the fifth seal observation season the local tourism providers have had to cancel. Experts expect the harp seals migration habits will simply adjust, but seal tourism in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence won’t fare as well.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

Environment

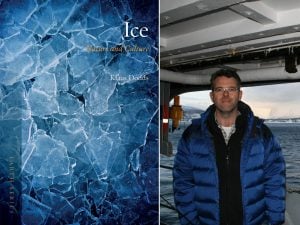

In his new book, Klaus Dodds delves into the fascinating natural and cultural history of ice

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

Environment

David Boyd, a Canadian environmental lawyer and UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, reveals how recognizing the human right to a healthy environment can spur positive action for the planet