Science & Tech

How Canada is preparing for the next big earthquake

The last megathrust earthquake to strike Canada was in 1700, and the clock is ticking. How we’re preparing for the impact.

- 2809 words

- 12 minutes

Environment

Think of the word “earthquake” and what likely comes to mind is someplace far away from Canada: Japan, perhaps, or New Zealand, or Nepal, all of which have experienced deadly and damaging quakes in the past 10 years. But Canada too is vulnerable to the shifting of Earth’s tectonic plates, and experts have long had their eye on one area in particular: the Cascadia subduction zone.

Stretching some 1,000 kilometres from northern Vancouver Island to California’s Cape Mendocino and located about 150 kilometres off the Pacific coast, the Cascadia subduction zone marks the boundary where the Juan de Fuca, Explorer and Gorda plates are slowly sliding beneath the larger, continental North American Plate. Although continually on the drift, the plates can sometimes become stuck when they come in contact, causing an immense buildup of strain that eventually overwhelms the friction between them. When that energy is released, an earthquake occurs. A big one.

Scientists have figured out that the Cascadia subduction zone experiences these “megathrust” earthquakes anywhere from every 200 to 800 years. The last one occurred in 1700, which means the next one could occur in another 500 years or so … or next week. For his new book On Borrowed Time: North America’s Next Big Quake, reporter Gregor Craigie spent a decade conducting in-depth interviews with geologists, engineers and planners about earthquakes: how we measure them, how we plan for them, and ultimately, how we survive them.

This exclusive excerpt from the book reveals the cross-cultural scientific detective work that exposed the catastrophic potential of the Cascadia subduction zone.

Meanwhile, Brian Atwater and his research team were gathering more evidence of past tsunamis. Atwater enlisted the help of David Yamaguchi, a dendrochronologist (tree-ring expert) from the University of Washington. Any log or tree stump has a pattern of thin and thick rings that show the sequence of droughts or strong growth over the tree’s life. To dendrochronologists, the rings form a sort of ecological barcode that can help scientists match one tree to another. Yamaguchi examined samples from the ghost trees that Atwater had found and embarked on painstaking counts of their rings to try to determine how old the trees were when they died. He then compared them to the rings of newly cut old-growth trees to learn when those long-dead trees died. Using tree-ring data and radiocarbon dating technology, he was able to determine that the trees died sometime in the late 1600s or early 1700s.

Atwater and Yamaguchi also uncovered evidence that the land itself had dropped suddenly. When Yamaguchi examined the roots of dead Sitka spruce trees they found, he discovered wide outer rings that told a tale of vigorously growing trees that were healthy right up to the time of their death. There was no sign of a prolonged death, such as from gradual saltwater poisoning or drowning, and this indicated a sudden event had killed the trees.

Atwater put this together with the rest of the evidence to show Cascadia had produced a major earthquake roughly three hundred years ago. Still, its size wasn’t clear. Could Cascadia shake as much as other subduction zones around the world? Was it capable of rupturing its entire length and triggering a massive magnitude-9 earthquake? To answer this crucial question, scientists went looking for clues in new places.

The rich oral histories of Indigenous peoples included stories from different villages of a great shaking followed by a huge wave that washed many people away. James Swan, an Indian agent and the first schoolteacher at the Makah Reservation in Neah Bay, Washington, kept a detailed diary of his years with the Makah, and in 1864 he recorded a story told to him by Billy Balch, the Makah’s leader — a story passed down through several generations. The ocean water, Balch said, rose up in Neah Bay and flooded the Waatch prairie. The water spread across the flat strip of land all the way to the other side of the cape and rejoined the Pacific Ocean a few miles away, effectively turning Cape Flattery into an island. The water then receded from Neah Bay, leaving it dry. After that, the water rose again “without any swell or waves and submerged the whole of the cape and in fact the whole country except the mountains back of Clyoquot,” Swan wrote. Balch told Swan that those who managed to jump into their canoes survived. They floated away in the strong current, with some making landfall at Nootka Sound on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island, where their descendants still live. But others drowned in the rapidly rising waters that stranded their canoes high in the trees. “The Waatch prairie shows conclusively that the waters of the ocean once flowed through it,” Swan concluded.

The Makah’s oral history bore a striking resemblance to tales from other Indigenous groups up and down the coast, from northern California to Vancouver Island. The stories were not written down until the 1860s, nearly fifty years after European settlement began and almost a century after the first European contact. By that time, scholars suggest, most oral traditions were likely lost, because of the large numbers of deaths from introduced diseases like smallpox and the disruption of family life that occurred when children were sent to residential schools. Still, Indigenous people shared stories of a frightening battle between Thunderbird and Whale that involved great shaking and flooding. The Tillamook people in northern Oregon recounted one of their stories to the anthropologist Franz Boas in the 1890s. “The Thunderer told him to stand aside,” Boas wrote, “as he himself was preparing to catch whales. He caught the largest one and carried it up to a large cave which was nearby, and when he had deposited it there the whale flapped its tail and jumped about, violently shaking the mountain so that it was impossible to stand upon it.”

Many of the Indigenous stories that anthropologists recorded between 1860 and 1964 are general in nature, but nine mention specific events that helped geologists estimate the date of the great earthquake, and some even specified the number of generations that had passed since the stories were first told. When geologist Ruth Ludwin eliminated the earliest and latest dates, she calculated an average midpoint of 1701.

Possibly the clearest Indigenous account of the great Cascadia earthquake was recorded in 1964, shortly after a gigantic earthquake in Alaska sent a tsunami wave surging up the Alberni Inlet on the west coast of Vancouver Island. The late Chief Louis Nookmis of Pachena Bay described a quake that struck many generations earlier. It came at night, he said, and was followed by a deadly wave soon after. “They had practically no way or time to try to save themselves. I think it was at night-time that the land shook….A big wave smashed into the beach. The Pachena Bay people were lost.” The Indigenous history completed a huge portion of the Cascadia Subduction Zone puzzle, but the final pieces came from a surprising location on the other side of the Pacific Ocean.

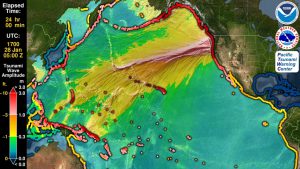

The word tsunami originated in Japan, with the prefix tsu translating as harbour and nami meaning waves. Japan is sadly familiar with this unique form of natural disaster. Japanese written history includes a long list of tsunamis, with the first one recorded in the year 684 CE. Many tsunamis have washed ashore in Japan over the years since, bringing death and destruction in varying degrees. Most followed great earthquakes that acted as warnings to the people living along the coast to run for higher ground. But written Japanese records also make occasional mention of orphan tsunamis that struck without warning. Orphan tsunamis are caused by massive subduction zone earthquakes that are too far away to be felt where the tsunamis eventually make landfall. The world’s biggest subduction earthquakes have claimed victims many thousands of kilometres away, such as the 1960 Chilean earthquake, which generated a tsunami that killed sixty-one people in Hilo, Hawaii, several hours later.

In the 1990s, geologist Kenji Satake at the Geological Survey of Japan heard about Brian Atwater’s work and wondered if one of Japan’s old orphan tsunamis might be connected to Cascadia. Satake found Japanese records of an orphan tsunami in the year 1700. It affected six towns and villages along a nine-hundred-kilometre stretch of coast on the main island of Honshu and did not correspond to earthquakes known to have occurred in South America, Alaska, or Kamchatka. Some samurai wrote detailed reports of a rising sea that came without warning in the middle of a winter night in late January 1700. The wave was recorded simultaneously in the villages of Kuwagasaki and Otsuchi, thirty kilometres to the south. Kuwagasaki lost thirty of its three hundred houses to tsunami waves up to five metres high and to fires that broke out afterwards. Villagers ran for high ground, and a request for help was sent to the nearby town of Miyako.

Knowing both the time the orphan tsunami struck and the angle at which it washed ashore led researchers to conclude it came from Cascadia and had started at roughly 9 p.m. local time on January 26, 1700. Scientists calculated that a wave large enough to reach Japan with such force would have sped across the Pacific Ocean for roughly ten hours before making landfall and must have been from a magnitude-9 or greater quake. Geologists could now fit the Japanese puzzle pieces into the picture and see the Cascadia Subduction Zone for what it really is: a massive undersea fault that has produced some of the world’s biggest earthquakes—and will do so again.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Science & Tech

The last megathrust earthquake to strike Canada was in 1700, and the clock is ticking. How we’re preparing for the impact.

Environment

David Boyd, a Canadian environmental lawyer and UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, reveals how recognizing the human right to a healthy environment can spur positive action for the planet

History

When the 'Big One' does occur, we will have little advance warning — but we will know what to expect.

Environment

The Canadian federal law regulating toxic substances has been updated for the first time in more than two decades