Wildlife

Excerpt from Takaya: The Lone Wolf

An enchanting and evocative look at the unique relationship between a solitary, island-dwelling wolf and a renowned wildlife photographer

- 1888 words

- 8 minutes

Wildlife

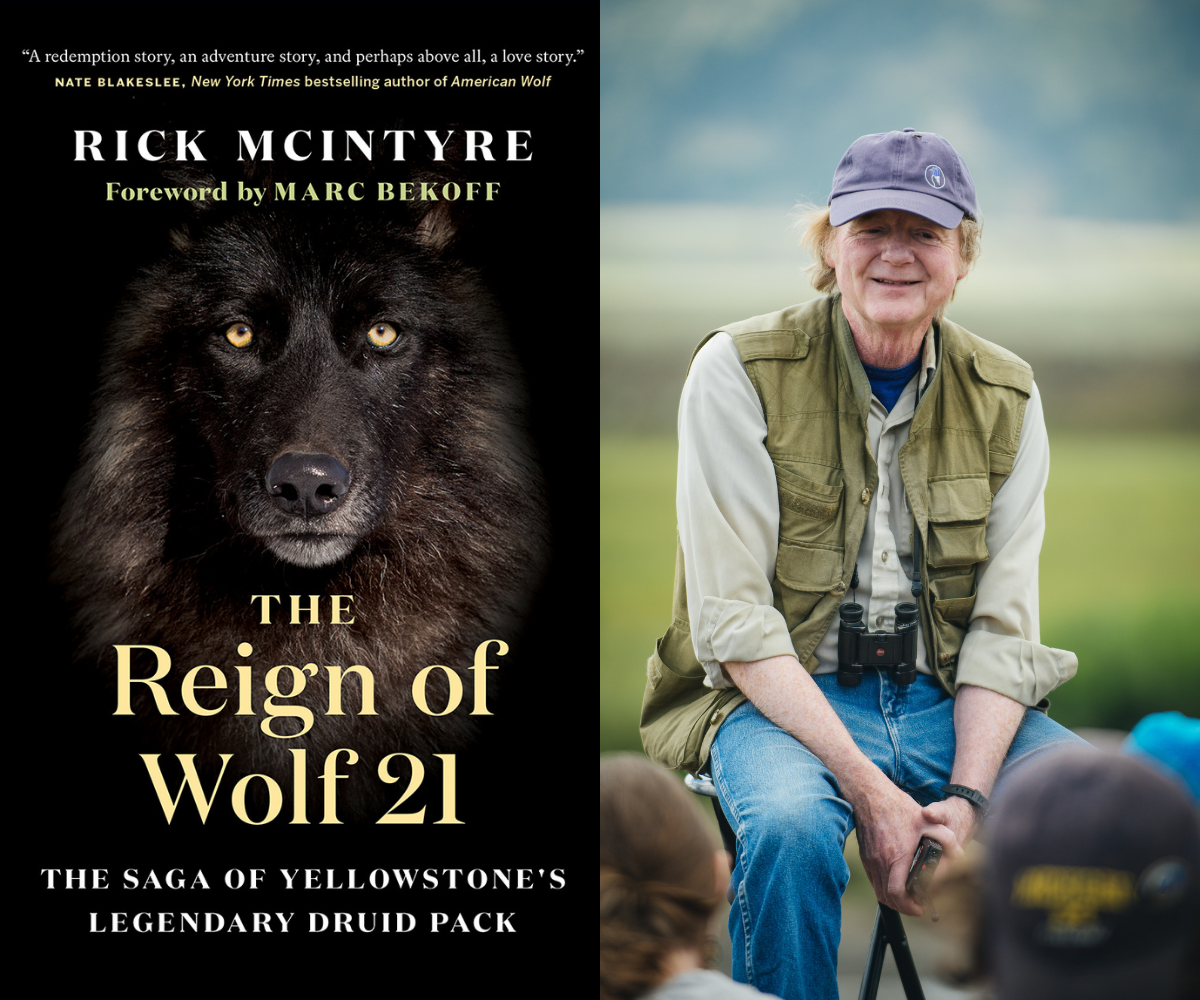

Wolf expert and bestselling author Rick McIntyre describes the relationship between Wolf 21 and Wolf 42 — alpha male and female of the Druids, the most successful wolf pack in Yellowstone history — and explains the positive impact of wolf reintroduction on the Yellowstone ecosystem.

On August 23, a Wolf Project flight found sixteen Druids back up at the Opal Creek rendezvous site: thirteen adults and the three pups. Since I had once hiked up toward that area and watched the Druids from a distance, I imagined 21 and 42 bedded down on the hill in the meadow. From that rise, they could watch over the pups as they played nearby. On the flight, Doug Smith got a mortality signal from Druid male 254 up the Lamar River, but thick trees prevented him from seeing anything on the ground. Doug and other staff hiked in and found the wolf’s remains among boulders at the base of a cliff. They concluded that he had fallen to his death. I later saw wolves confronting elk on cliff tops. 254 had probably done the same thing and either got too close to the edge and slipped or was kicked by an elk and fell.

The three Druid pups were back at the Chalcedony Creek rendezvous site the following day. 42 wrestled with one and played tug-of-war with another. She was well over seven years old now, about sixty in human years, but she still had a playful spirit. Later she ran to 21 and affectionately licked his face. The two had been together now for nearly five years, about the same length of time as the entire life-span of an average Yellowstone wolf.

21, like 42, was getting old. Despite his advancing age, he often acted like a much younger wolf. One day he caught a vole and tossed it in the air several times. After the last throw, he touched the tiny rodent with his nose, then immediately jerked his head away. The vole must have bitten him. After that he picked it up, carried it around, then dropped the vole and playfully pawed at it. At that point, the black pup came over, hoping to get the toy from his father. Wanting to prolong the game, 21 grabbed the vole, carried it off, bedded down, and resumed playing with it. The pup joined him, then lay down a few inches from the vole and 21’s face. Several other wolves approached and 21 made the mistake of turning his head to look at them. The pup, waiting for just such a moment, darted in, grabbed the vole, trotted off, and tossed it into the air. Then she ate it. After that 21 played with the big gray female pup. They wrestled and he made it seem like they were evenly matched. She snapped at him and bit at the fur on his face. When she ran off, the big alpha male romped after her. They continued to wrestle and spar, and later 21 played the ambush game with her.

By late August, it was getting harder to find the Druids. Although they occasionally showed up at the Chalcedony Creek rendezvous site, they spent most of their time out of sight up on Specimen Ridge.

Elena West, a Wolf Project staff member, and I hiked up the Lamar River in early September. We had seen the Druids investigate an active beaver lodge there the previous June. The unusually high water in the spring had destroyed most of the structure. The family had made a bad choice of location for the lodge and abandoned the site. There was no sign that any beavers were still in the area.

On the way back, I noticed how well the willows were doing along the river and at nearby Soda Butte Creek, where there was a new beaver colony, perhaps started by the family that had lived upriver. Beavers rely on willows close to their lodges as their primary food supply, and the willows were rebounding after years of heavy browsing by elk. In a meadow near Pebble Creek Campground, the willows were growing especially wide as well as tall, up to fifteen feet.

I regularly hiked up Crystal Creek to where one of the wolf acclimation pens had been built. I led nature hikes up there for several summers after the 1995 wolf reintroduction and showed people how elk had killed thousands of aspen shoots by overbrowsing them. Now the young aspens in that area were twenty feet tall and as thick as a bamboo forest. That month I talked with a vegetation researcher who had 113 study plots in the local area. He found that aspen shoots were an average of twelve centimeters higher in areas where wolves were common compared with plots without wolves. He interpreted that to mean that elk were spending less time browsing on aspen shoots in areas where wolves were frequently encountered.

More importantly there were fewer elk in the park. Wolves, along with mountain lions, were the main predators of elk when Yellowstone was set aside in 1872. The early rangers killed off the last of the original wolves in 1926 and shot the last lions in the 1930s. In the absence of those predators, elk multiplied to an overpopulation level that did great damage to the vegetation they fed on, especially willows, aspens, and cottonwoods. Now, with the reintroduction of wolves, predation by grizzlies and cougars, and increased human hunting of elk adjacent to the park, elk numbers were in better balance with food supplies. With fewer elk in the park, willows, aspens, and cottonwoods were recovering, and that benefited other plant-eating animals such as bison and moose, as well as beavers. The restored vegetation also provided additional habitat for songbirds.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Wildlife

An enchanting and evocative look at the unique relationship between a solitary, island-dwelling wolf and a renowned wildlife photographer

Wildlife

An estimated annual $175-billion business, the illegal trade in wildlife is the world’s fourth-largest criminal enterprise. It stands to radically alter the animal kingdom.

Wildlife

Exploring our love-hate relationship with the wolf

Wildlife

This past summer an ambitious wildlife under/overpass system broke ground in B.C. on a deadly stretch of highway just west of the Alberta border. Here’s how it happened.