Environment

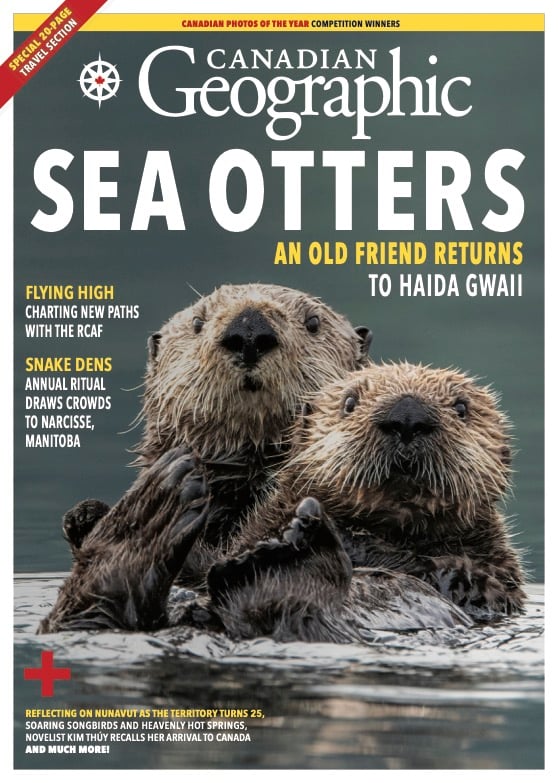

Bioplastics: Don’t let the label fool you

Doing your part as an eco-conscious consumer doesn’t end once you buy a bioplastic product

- 1626 words

- 7 minutes

Environment

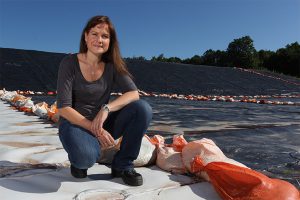

The environmental journalist and television personality dives into the complexities of sustainable living in a new book

Candice Batista wants to change the way we shop. The way we clean. The way we decorate, cook, garden, recycle — basically, everything.

A writer, producer and fixture on Toronto-area cable television for over 20 years, Batista regularly appears on Cityline and Breakfast Television to share her tips for eco-friendly living, from how to properly recycle your takeout pizza boxes (cut off and compost the greasy part) to how to make your own reusable disinfectant wipes. Now, she’s compiled those tips into a book, Sustained, to guide Canadians toward better understanding how our daily routines and purchasing decisions impact the environment, as well as a better sense of how we can reduce household waste (and save money in the process).

About 15 years ago, I took a leap of faith and left my job at the Weather Network to launch a television series on Rogers Cable 10 called A Greener Toronto. It looked at how Torontonians were fostering environmental stewardship in many ways, from organic food and regenerative agriculture to composting, waste diversion, ethical fashion and reducing textile waste. It was well received, but it was way ahead of its time. [When talking about environmental issues in mainstream media], a lot of times you’re in a precarious position because the advertisers are part of the problem. You’re always navigating this very fine line between your own ethics and biting the hand that feeds you.

Sustainable living is not easy to navigate, especially in our current system. It’s like a Groundhog Day of consumption; we’re stuck in this awful loop and we just can’t stop consuming stuff. The idea is just to start somewhere. The ultimate goal of living sustainably is to live frugally. It’s to understand your impact. I always say, “Do it like your granny did it.” Our grandparents would never have envisioned that we would buy a product like a garbage bag or a dryer sheet or a paper towel strictly to throw it out.

I often get comments like, “I’m not bothering with this” or “why should it be on the consumer [to make change]?” But it’s not about one person making a difference; it’s one person trying to reach another person who then reaches another person. Ten years ago, when people started demanding more transparency around the ingredients in beauty products, everybody was like, oh, this is a flash in the pan; it’s just marketing nonsense. But ultimately, it revolutionized the beauty industry. Today, the green beauty industry is worth billions of dollars, and you have massive companies like Procter & Gamble buying small indie skincare companies because they want in on that action. It shows what can happen when people come together and demand better.

I wanted to put as much information in the book as I could, because living sustainably is so nuanced. Part of the problem is that we don’t have clear definitions for certain things. Consider sustainable fashion as an example. To me, that might mean ethically manufactured — no workers were harmed, they were getting fair wages. But to you, it might be that the clothing contains no toxic chemicals. You’ll see products with labels like cruelty-free, vegan, eco-friendly, green, sustainable, natural, non-toxic, oil-free, sustainably sourced, biodegradable, but what do any of these things mean? I also wanted to provide a framework for what to keep in the back of your mind [when a product claims to be sustainable]. The first thing is, what is that item made of? The second thing is sustainable sourcing and ethical manufacturing: who made my clothes? Who made my skincare? Who picked my coffee beans? And then the third thing is looking at corporate responsibility: what are companies actually doing to make a difference? Do they offer carbon offsets? How are they shipping? Do they have repair or resale programs? My thinking was, “How can you actually go into the world after you’ve read all this and navigate trying to shop sustainably or just be sustainable in your everyday life?”

Part of the problem is we’re so disconnected from each other and from nature. We don’t know where our food comes from. We don’t know where our garbage goes. We have so much stuff, we can’t find our stuff. We’re in this consumption mindset because we’re constantly bombarded with advertising. “Sustainable living” has become a catchphrase, but it’s not about buying the newest sustainable product. You do not need to buy beeswax wraps. The most sustainable product is what you already have in your home.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the March/April 2024 Issue

Environment

Doing your part as an eco-conscious consumer doesn’t end once you buy a bioplastic product

Environment

Myra Hird, a sociology professor at the School of Environmental Studies at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., discusses why recycling isn’t a perfect solution

Environment

Canada leads the developed world in per capita production of garbage. What’s behind our nation’s wasteful ways?

Science & Tech

Environmental entrepreneur Miranda Wang turns to science to seek profitable solutions to the problem of what to do with our mountains of plastic waste