History

2014 Victoria Strait Expedition

This year's search is about much more than underwater archaeology. The Victoria Strait Expedition will contribute to northern science and communities.

- 1205 words

- 5 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

History

Imagine dodging large blocks of ice and having the warmth sucked out of your body while scouring a never-before-seen part of Earth.

That’s how Ryan Harris, chief underwater archaeologist for Parks Canada, describes his experience searching for Sir John Franklin’s lost ships in Canada’s Arctic.

The quest to find the ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, from Franklin’s tragic 1845 expedition — a pivotal moment in Canada’s history on Arctic sovereignty — will begin where it left off.

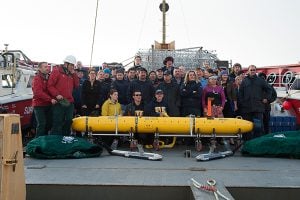

Building on the momentum from the last five years of searching, a group of Parks Canada divers and other researchers will join public and private partners setting out on the cold, icy waters this month.

For two weeks, the team will be surveying in Victoria Strait, a large body of water west of King William Island. “If the weather cooperates and the ice doesn’t get in the way, we hope that we might cover as much as 1,400 square kilometres,” Harris says.

The expedition will move north to where the team believes the ships were abandoned. The water will get colder and deeper, reaching depths of 150 metres.

Searching for the lost ships is an intensive endeavour. An underwater sonar will be scanning large blocks of the sea floor in a zigzag manner. If the sonar detects something, the team will deploy a vehicle with cameras to check out the find. If there appears to be something promising, the divers will take a look.

“After years of staring at the side scan sonar screen watching the sea floor scroll by hour after hour, I can only imagine the exhilaration of actually seeing something we could take a closer look at,” Harris says.

In his experience scanning the Arctic sea floor, Harris has developed a good sense of what things look like. He says the Erebus and Terror would probably be intact if the ice has not reached them. “If located in shallow water, there would be the potential for ice keels to rake over the wreck site, split it apart and smear it over the sea floor.”

But the search team has already surveyed most of the shallow areas. “As we search farther north, if we locate a wreck between our existing coverage and where the ships were abandoned in 1848, that’s going to be deeper water, which will increase the odds of that particular wreck surviving, hopefully in remarkable condition.”

And these are no ordinary ships; they were built for endurance. “They were heavily fortified by the Royal Navy for Arctic service.”

Harris says locating the ships is just the tip of the iceberg. “The process of archaeology is long.” If this year’s team does find the shipwrecks, a very intensive examination of the site will be made. They will try and determine which artefacts are present and the integrity of the hall. Researchers would then study the artefacts and examine what they tell us about the final moments.

“Canadians would be acquainted with an absolute national treasure,” he says.

Harris is feeling pretty confident that the team will find the lost ships this year. “This is the largest effort to date.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

History

This year's search is about much more than underwater archaeology. The Victoria Strait Expedition will contribute to northern science and communities.

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

History

Why this summer’s search for the lost ships of the Franklin Expedition will be the biggest and most advanced ever

History

Arctic historian Ken McGoogan takes an in-depth, contemporary perspective on the legacy of Sir John Franklin, offering a new explanation of the famous Northern mystery