Wildlife

Why won’t wolverines cross the road?

In shedding light on wolverines’ aversion to roads, new research suggests the key to their conservation in Alberta

- 844 words

- 4 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Travel

“There seemed few outlets left for the restlessness that ached inside me, this mad longing for a world without maps,” writes Canadian explorer Kate Harris of her teenage wanderlust in the opening chapter of her debut travel memoir, Lands of Lost Borders. That urge to go beyond the places “circumscribed by an expanding network of highways and subdivisions” led the then 17-year-old Harris to send 22 world leaders a letter urging a human mission to Mars, which she had long dreamed of going to.

And while Harris herself eventually did visit the Red Planet — after a fashion, anyway — it wasn’t quite as tangible as she had imagined it would be, prompting her to turn her sights back to Earth and another childhood dream destination: the fabled Silk Road trade route, which she cycled the length of with her childhood friend, Melissa Yule, in 2011.

One of the results of that much more palpable journey — the shifting sands of the Taklamakan Desert, a 10-year-old Turkish girl painting Harris’s fingernails hot pink, shopping for instant noodles in Uzbekistan — is Lands of Lost Borders, which is published today.

Read the prologue to Lands of Lost Borders below and then check out Canadian Geographic’s Facebook page for a chance to win a copy of the book.

***

The end of the road was always just out of sight. Cracked asphalt deepened to night beyond the reach of our headlamps, the thin beams swallowed by a blackness that receded before us no matter how fast we biked. Light was a kind of pavement thrown down in front of our wheels, and the road went on and on. If I ever reach the end, I remember thinking, I’ll fly off the rim of the world.

I pedalled harder.

The evening before, Melissa and I had carefully duct-taped over the orange reflectors on our wheels. Just after midnight, we’d crawled out of our sleeping bags, dressed in black thermal long underwear, packed up camp, and mounted our bicycles. As we rode toward Kudi, a tiny outpost in western China, only our headlamps gave us away, two pale flares moving against the grain of stars. We clicked off the lights as we neared the town.

It was three a.m. and moonless. The night air was cool for July and laced with the sweet breath of poplars and willows that grew in slender wands beside the river. No clean divisions between earth and sky, light and dark, just a lush and total blackness. I couldn’t see the mountains but I could sense them around me, sharp curses of rock. The kind of country that consists entirely of edges.

Sometimes Mel and I drifted blindly into each other, our bulky panniers acting like bumpers. We navigated by the sound of our wheels, a hushed whirring indicating the pavement, a rasp of gravel the road shoulder and the need for a course correction. Travelling by bicycle is a life of simple things taken seriously: hunger, thirst, friendship, the weather, the stutter of the world beneath you. I was so focused on listening to the road that I didn’t notice the glint of metal until Mel did.

“That’s it,” she whispered. “The checkpoint.”

A guardrail scissored the road ahead, and somewhere beyond it, mythic and forbidden, was the Tibetan Plateau. Though Kudi isn’t technically in the Tibet Autonomous Region, or TAR, as China has designated the formerly sovereign nation, the village hosts the first and most formidable military checkpoint on the only road into the western part of Tibet, a place foreigners require permits and guides to visit. Mel and I had neither. We didn’t want to subsidize the Chinese occupation of Tibet by paying to go there, and we lacked the money for permits anyway. Plus, we’d just graduated from university and felt young and free and rashly unassailable: never once had we met a barrier we couldn’t muscle past. So we took a deep breath, looked both ways, and biked directly under the raised guardrail.

Nothing happened. Somewhere to my left a river sounded like wind. The stars looked freshly soldered above the dark metal of the mountains, faintly visible now that our eyes had adjusted. Mel was a whim of shadow to my left but I could feel her giddiness, or maybe it was my own, adding a kind of shimmer to the air. The world seemed preternaturally honed and heightened, our vision and hearing sharper. I watched a star shoot to the horizon with an afterimage trailing behind it. “Did you see that?” I whispered. When that same star shot up again, we shoved our bikes into the ditch and ran.

The flashlight scanned the road, moving closer in clean yellow sweeps. Mel dove into the ditch a few metres from our bikes and I bolted senselessly toward the nearest building, where I flattened myself against a wall. I heard footsteps approach, the click of heels on concrete, and regret seared me. I would never be a Martian explorer now. Instead I’d spend the rest of my days in a Chinese prison, desperately wishing I had something to read. With my cheek pressed against concrete, I stared up. If the heavens aligned, I told myself, if a single constellation clicked into place—the Big Dipper, say, or Cassiopeia—we’d be saved. I scanned the night sky for some reassuring sign, any familiar map to orient myself by— ironic, I suppose, when the great goal of my life was getting lost. But the stars reeled and spun and refused all their usual patterns. The footsteps came closer and closer and stopped.

Then I spotted the Big Dipper pouring out the sky. The footsteps started again, moved closer, and faded away. I didn’t dare move or breathe or glance at Mel, who was still playing dead somewhere in the ditch. A few minutes or an eternity later a truck sputtered into gear and drove off the way we’d come. The night settled back into silence.

We grabbed our bikes and continued racing through Kudi, instantly unrepentant. Fear exhausted itself into euphoria, a sense of irrational hope. The man with the flashlight surely saw us, pathetic and full of prayers in the ditch and against the wall, a couple of dogs with our heads tucked under the couch, believing our whole bodies hidden. At the very least he must have spotted our bikes overturned in the ditch, their wheels spinning uselessly.

Why he decided to move on was a mystery we didn’t question, in part because we were too winded to talk.

But even as Mel and I pedalled hard toward the Tibetan Plateau, I noted the bomb-like ticking of excess reflector duct tape against the front fork of my bike. Tick-tick-tick-tick-tick, the sound went, a gentle yet ominous stutter. I should trim that, I thought to myself. That’s when a second checkpoint, the real checkpoint, loomed from the darkness like a bad dream. This time the guardrail was lowered, thigh-high, and secured with chains. Lighted concrete buildings edged the checkpoint on both sides, though we couldn’t see anyone in them.

“Um…” I stopped pedalling, letting my bike coast and slow.

“Yeah…” Mel acknowledged, but her voice came from somewhere ahead of me.

I hesitated for a beat and started pedalling again. If Mel wasn’t about to back down, neither was I. “Throw your heart over the fence,” our Pony Club instructors had always urged us, “and the rest of you will follow. Hopefully the horse and saddle too,” they’d add with a grin. The only way to test the truth of a border is to ride hard toward it and leap — or, if circumstances demand it, crawl. Exposed in the pale light leaking from the checkpoint buildings, Mel and I glanced at each other one last time. Then we scuttled on hands and knees beneath the guardrail, dragged our loaded bikes after us, and pedalled as fast as we could into forbidden territory.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Wildlife

In shedding light on wolverines’ aversion to roads, new research suggests the key to their conservation in Alberta

Environment

An estimated 29 million mammals are killed each year on European roads

People & Culture

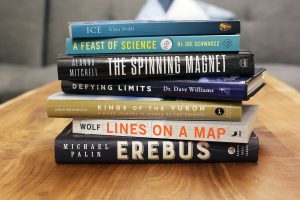

Memoirs, a graphic novel and the biography of a famous ship are among Canadian Geographic's choices for the 14 best books of the year

People & Culture

An exclusive Q&A with British explorer, comedian and actor Michael Palin