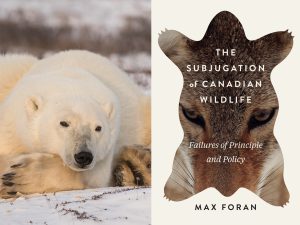

New Canadian research confirms polar bears use crosswinds to sniff out their food

It’s an idea that seems as plain as the nose on a polar bear’s face. But researchers at the University of Alberta have proven that the animal uses its sense of smell to track prey, marking the first time that crosswinds have been shown to play a role in how a mammal hunts.

Researchers Ron Togunov and Andrew Derocher recently published the results of an 11-year study that merged polar bear movements with wind patterns on Hudson Bay.

Ringed seals, the bears’ preferred meal, give birth out of sight, hidden under layers of snow. Researchers knew that polar bears used their sense of smell to find the hidden seals, but Togunov says, “how they use that sense of smell had only been theoretical.”

Togunov and Derocher used satellite telemetry for their study, which allowed them to track both the movements of the wind and 123 polar bears simultaneously.

“Predators search for prey using odours in the air, and their success depends on how they move relative to the wind,” explains Togunov. “Traveling crosswind gives the bears a steady supply of new air streams and maximizes the area they can sense through smell.”

Now Togunov is looking at how wind speed affects the way polar bears hunt. As the Earth warms, the speed of Arctic winds is projected to rise and researchers predict this could make it harder for polar bears to find food. “Fast winds are associated with a decrease in foraging,” he says. “They make it more difficult for the bears to find the source of the smell they detect, but I don’t know at which wind speed it’s actually unfavourable.”

“We can’t conclusively say what effect it’s going to have on the bears,” he added, because “we don’t know how big of a role wind is playing. But we can say it’s definitely not going to be good.”