History

Royal Canadian Geographical Society CEO John Geiger gives a sneak peek of this year’s Franklin search

Why this summer’s search for the lost ships of the Franklin Expedition will be the biggest and most advanced ever

- 1638 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Harsh arctic conditions, such as those that defeated Sir John Franklin, are exactly what David Hopkin needed this summer to test some sophisticated Canadian undersea technology. Hopkin, a scientist with Defence Research and Development Canada, tried out some cutting-edge sonar imaging equipment in Nunavut as part of the 2014 Victoria Strait Expedition. His experiments met with resounding success.

With more ships going to the North every year, accurate maps are needed for Canada’s mostly uncharted Arctic waters. To make these maps, cartographers rely on pictures of the sea bottom, and the more detailed these are the better. High-quality images also make it easier to find objects on the sea floor, whether a historic shipwreck or the flight data recorder from a downed aircraft.

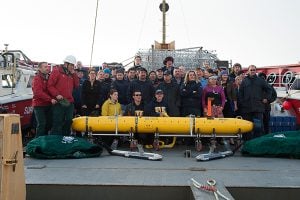

Hopkin and his team were testing what turned out to be a potent combination: the Arctic Explorer autonomous underwater vehicle and its onboard interferometric synthetic aperture sonar, which takes crystal-clear pictures using sound. “Synthetic aperture sonar takes very high-resolution images,” explains Hopkin, “but this system had never been tried in conditions where 100 metres down you have sub-zero water temperatures.”

The yellow, torpedo-shaped Arctic Explorer, which is 7.4-metres long, can travel under the ice for several days, covering distances of hundreds of kilometres. It navigates its programmed course independently — operators have no control over the vehicle during the mission — looking for particular features or objects by taking high-resolution sonar images of the sea bottom. Then it returns to base. This is straightforward when the base is stationary, but challenging when it’s on floating ice, which may have drifted far from its original position. This is where precise sonar comes in, and it’s a bit like whistling for a dog. The operators send out an audible signal that the sonar system “hears” and homes in on as it guides Arctic Explorer back to the base in its new location.

Though Hopkin and his team weren’t the ones to find the Franklin shipwreck (their search area was far north of where it lies), they were nonetheless delighted with the results of their part in the expedition. “This is the only technology of its kind in the world and it performed flawlessly in Arctic conditions,” says Hopkin. “Thanks to the new system we now have the clearest, most exciting imagery of this part of the world to date. We showed that with the Arctic Explorer and synthetic aperture sonar, both made in Canada, we can now explore unknown, uncharted areas of the Arctic Ocean floor under the harshest conditions.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

History

Why this summer’s search for the lost ships of the Franklin Expedition will be the biggest and most advanced ever

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

History

This year's search is about much more than underwater archaeology. The Victoria Strait Expedition will contribute to northern science and communities.

History

Arctic historian Ken McGoogan takes an in-depth, contemporary perspective on the legacy of Sir John Franklin, offering a new explanation of the famous Northern mystery