People & Culture

Kahkiihtwaam ee-pee-kiiweehtataahk: Bringing it back home again

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

- 6310 words

- 26 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

Josiah Henson was born into slavery in the United States in 1789. By 1852, his dictated Canadian memoir, The Life of Josiah Henson Formerly a Slave, would help to inform one of the most popular books of the era, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The novel, which channeled Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery ideals, sold more than 300,000 copies in its first year of print and was recognized by President Lincoln as a catalyst of the American Civil War.

The life lived by Josiah Henson between those moments and beyond are explored at Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site in Dresden, Ont., the place he called home for much of his free life.

It’s a complicated story.

Over the course of Henson’s life, he was a slave, fugitive, refugee, community builder, conductor on the Underground Railroad (which brought between 30,000 and 40,000 fugitive slaves to Canada), preacher, author and abolitionist.

But he was also an overseer — at one time he was responsible for reporting on the actions of other black slaves to his white masters on a plantation in Maryland. After Beecher Stowe’s novel, minstrel shows popped up across Canada and the United States where white actors in blackface would perform racist depictions of step-and-fetch-it, unintelligent “Uncle Tom” characters to the delight of white audiences.

“[In the shows] Uncle Tom was a sellout,” explains Brenda Lambkin, assistant manager at the historic site. “Those shows ran for 70 to 80 years. That’s a lot of ingraining in people that Uncle Tom wasn’t any good.”

That reputation is one of the reasons why Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site aims to present a more layered telling of Henson’s story. Artifacts, film clips, preserved buildings and story boards trace his harrowing journey with his wife and four children from slavery in Kentucky to freedom in Ontario in 1830 (sometimes literally carrying his family on his back). Exhibits detail his involvement in the founding of the British American Institute in 1841, a trade school attended by Underground Railroad refugees, and the Dawn Settlement, which provided housing to former slaves, both in Dresden, Ont., as well as the more than 118 people he guided to freedom in Canada through the Underground Railroad.

Henson died in 1883 at the age of 94, and both his last home and his grave are located on the historic site. Every August, Emancipation Day celebrations at the historic site commemorate the end of slavery in Canada and bring together slave descendants who trace their history to the area.

As Canadians, says Lambkin, we’ve dropped the story of black history in this country. “We need to pick it up and show our children we have something to be proud of.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

*It means “awake” in Beothuk, the language and people who once called present-day Newfoundland home for about 2,000 years. One young woman, believed to be the last living Beothuk, left a collection of maps and art that help us understand her people’s story.

Environment

Struggle and success in Atlantic Canada, where aquaculturists strive to overcome climate change and contamination while chasing a sustainable carbon footprint

Travel

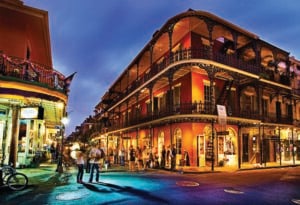

A tour of the Big Easy’s distinct neighbourhoods offers plenty of insights into the city’s storied past