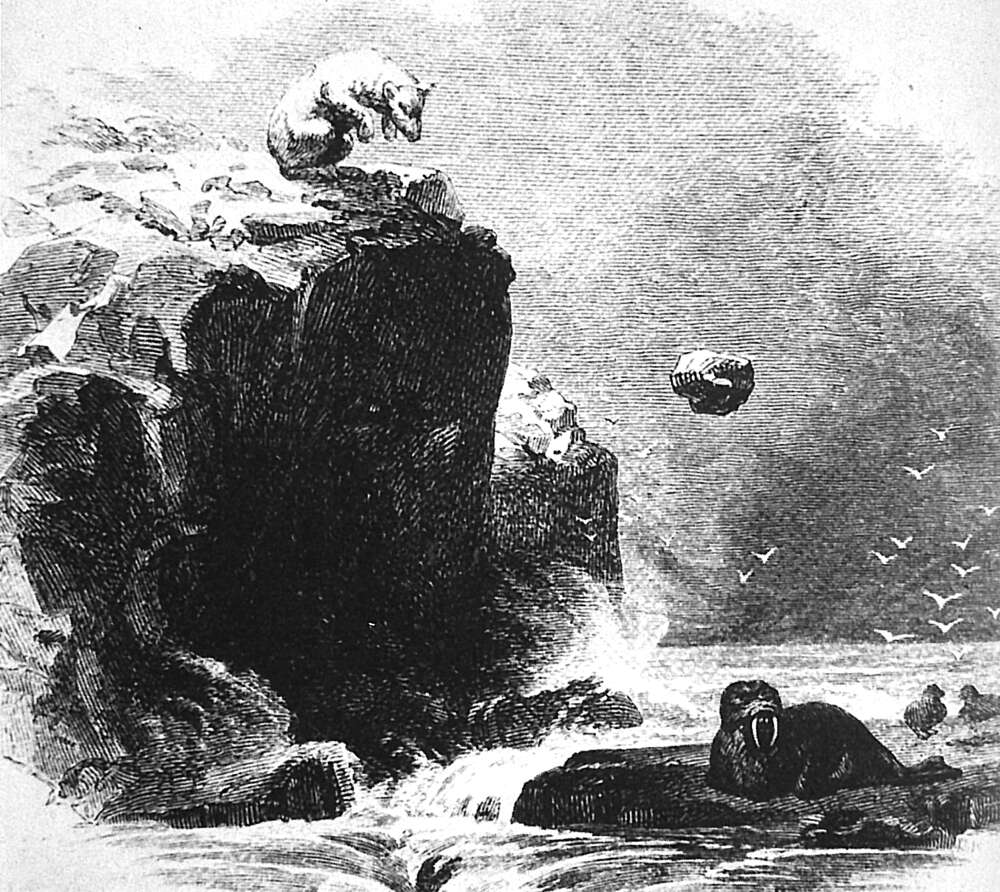

“Bear killing walrus,” an 1865 engraving by explorer Charles Francis Hall, appearing in his book Arctic researches and life among the Esquimaux being the narrative of an expedition in search of Sir John Franklin in the years 1860, 1861, and 1862 (Illustration: Charles Francis Hall)

Polar bears aren’t just powerful hunters through sheer force; recent research confirms they also use tools to kill walruses, striking them over the head with pieces of ice, or hurling rocks at them. It’s something that Inuit hunters have known and reported for hundreds of years — and indeed, the researchers who authored the study in the journal Arctic worked closely with Inuit, drawing on traditional ecological knowledge as well as documentation by Inuit hunters and scientists. In 1865, explorer Charles Francis Hall made an engraving showing what his Inuk guide told him: “In August, every fine day, the walrus makes his way to the shore, draws his huge body up on the rocks, and basks in the sun. If this happen [sic] near the base of a cliff, the ever-watchful bear takes advantage of the circumstance to attack this formidable game in this way: The bear mounts the cliff, and throws down upon the animal’s head a large rock, calculating the distance and the curve with astonishing accuracy, and thus crushing the thick, bullet-proof skull. If the walrus is not instantly killed—simply stunned—the bear rushes down to the walrus, seizes the rock, and hammers away at the head till the skull is broken.”

The historical and modern evidence was corroborated by observations of polar bears in captivity, showing that the bears are capable of using tools to access food sources. The researchers, led by Ian Stirling of the University of Alberta, suggest that this hunting behaviour is infrequent and limited to walruses because of their size, difficulty to kill and the possession of their own weapons (their tusks).