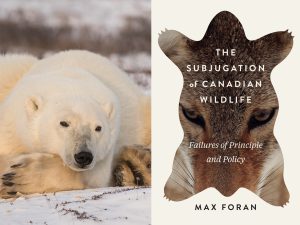

That’s led to an unrelenting cascade of negative effects on the polar bears of western Hudson Bay, one of the most southerly of the world’s 19 subpopulations. Pregnant females weigh less than they did in the 1960s, and all females are shorter, according to long-term research by biologists Ian Stirling and Andrew Derocher. Fewer are producing young. Those that produce young have fewer cubs. Survival of those cubs has dropped like a stone, and the ability of a yearling cub to survive without its mother has vanished, which further impairs the mother’s ability to become pregnant again. The population has shrunk by about a third since the mid 1990s.

And the future looks grim, here and elsewhere in the Arctic. There’s only so much fasting a polar bear can do. Eventually, the bears of western Hudson Bay will be too thin to have any young, according to a recent study by biologists Péter Molnár and Stephanie Penk of the University of Toronto, and others.

“If you have a population that can’t reproduce, you have a population that can’t survive, right?” Penk tells me later when I reach her in Texas by Zoom.

By the turn of the century, unless carbon trajectories change drastically, all but the most northerly polar bears on Earth will be dead, the victims of climate heating, her study found. In Churchill, they will be just a memory.

Tourists in Churchill are aware that this global icon of climate change is in peril. They fly here in droves to see one in the wild before it’s too late. Researchers call the treks “last-chance tourism” or “doom tourism.”

“The irony of us emitting greenhouse gases to go visit species that we’re essentially killing by emitting greenhouse gases is very thick,” says Jackie Dawson, Canada Research Chair in the Human and Policy Dimensions of Climate Change and a science director for the climate change research network ArcticNet.

Here in Churchill, I still haven’t spotted a bear. Miller offers to drive me around the bear-resistant garbage facility. It opened in 2005, after the town shut down the dump where hungry bears once congregated to feast on refuse, and is a key to more congenial relations between humans and bears. Carefully, we go outside to her truck, scanning for anything that moves. Miller carries bear spray, which, she tells me coolly, is highly effective against polar bear attacks.

Down the highway we drive, toward the airport. Past the garbage facility, where a bear was sighted recently. Down a backroad to where Miller knows bears often lounge. Nothing. And then around to the polar bear holding facility, a vast, corrugated metal structure whose hulking shape is reminiscent of a sleeping bear, stark against the expansive sky. In fact, a supersized sleeping bear is painted on its front face, a reminder of how the animals dominate the iconography of the town.

Bears are inside the jail today, but not outside. A busload of tourists — among the last of this season — has just pulled up, and the excited crowds are milling around the structure, taking selfies and grinning.

Miller and I cruise around a little more. No bear. Yet.