One hundred years ago this autumn, a group of men set out across the ragged, barren icescape of Antarctica to search for the dead. They’d been out for 15 days when, on Nov. 12, 1912, the party’s navigator, Charles Wright (right), spotted something sticking out of the snow about 800 metres to the west. Skiing over to it, Wright realized he’d found what they’d been looking for. He waved the search party over, and the men stood around the patch of frozen tent canvas for a moment before digging the snow away. Peeling back the flap, they discovered the body of Captain Robert Scott and two others, Henry Bowers and Dr. Edward Wilson. Scott’s left arm lay across Wilson, and his three notebooks were found under his shoulders. The final entry read: “For God’s sake look after our people.”

The story of Scott and his doomed bid to be the first person to reach the South Pole is one of polar exploration’s most famous — and tragic — tales. Scott’s death made him a posthumous hero, but without Wright, the sole Canadian on the expedition, the fate of the British explorer likely would have remained a mystery.

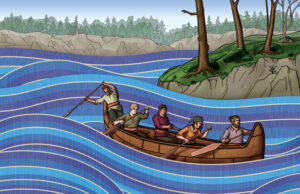

Born in Toronto in 1887, Wright was an explorer from an early age, spending entire summer vacations canoeing through remote regions of Northern Ontario with his two brothers. Being accepted to Cambridge for post-graduate studies in physics in 1908 didn’t dampen his enthusiasm for adventure, and in 1910, he applied for a position as physicist on Scott’s second expedition to the Antarctic. He was rejected but did not give up, walking 80 kilometres from Cambridge to London to resubmit his application to Scott in person. Wright walked away as the expedition’s chemist and physicist and later was named the team’s glaciologist.

Scott and his men reached Antarctica’s Ross Island aboard the Terra Nova in January 1911. Ten months later, on Nov. 1, Wright found himself on the 16-man team that was racing Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen to be the first to reach the South Pole. The frigid weather and uneven ice surfaces made the drive to the pole brutal, however; four men had been sent back by early December, and on Dec. 20, Scott ordered Wright and three others to return to Ross Island while he and seven men continued. None of them could have known that Amundsen had reached the pole six days earlier. Three more men were sent back on Jan. 4, 1912. It was the last day Scott and the remaining four men were seen alive. By April, it was apparent that they must have died, but the vicious Antarctic winter meant that a search party couldn’t set out until October.

Scott’s diary revealed that the team had made it to the South Pole on Jan. 17, only to find Amundsen’s flag already planted. Exhausted, dejected and with supplies dwindling, they began the long trek back to base camp. One of his men, Edgar Evans, died on Feb. 17 and was buried. A month later, Lawrence Oates, who had a badly frostbitten foot, walked out of the tent, never to be seen again. The bodies of Scott, Bowers and Wilson were left where they had been found; the search party buried the tent under a snow cairn topped with a cross.

It took Wright nearly 50 years to return to Antarctica and finally reach the South Pole. When he did, aboard a U.S. Navy flight in 1960, it was as Sir Charles Wright, an eminent scientist who had helped develop wireless trench communications, radar and, during the Second World War, a device that could detect magnetic mines and torpedoes, for which he received his knighthood.

“He was not one to dwell on the past unless others pressed him,” says Fred Roots, a Canadian polar scientist. “My impression was that Wright was the kind of person described by Robert Service as one who had ‘done things just for the doing, letting babblers tell the story.’”