People & Culture

On thin ice: Who “owns” the Arctic?

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

- 4353 words

- 18 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

Canadians watched in horror last summer as one North Atlantic right whale after another was found dead around the Gulf of St. Lawrence, washed up on beaches or floating offshore, apparent victims of ship strikes or fishing gear entanglements.

Scientists think part of the problem may stem from the whales moving into new territory in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in search of food, where they instead encounter busy shipping lanes and commercial fishing zones. This set of circumstances, driven at least in part by climate change, is raising alarm bells about other whale populations living a long way from the Gulf. In Canada’s Arctic, warming waters and longer ice-free seasons driven by climate change are creating the conditions for a major increase in shipping and potentially even fishing in waters heavily used by whales and other marine mammals.

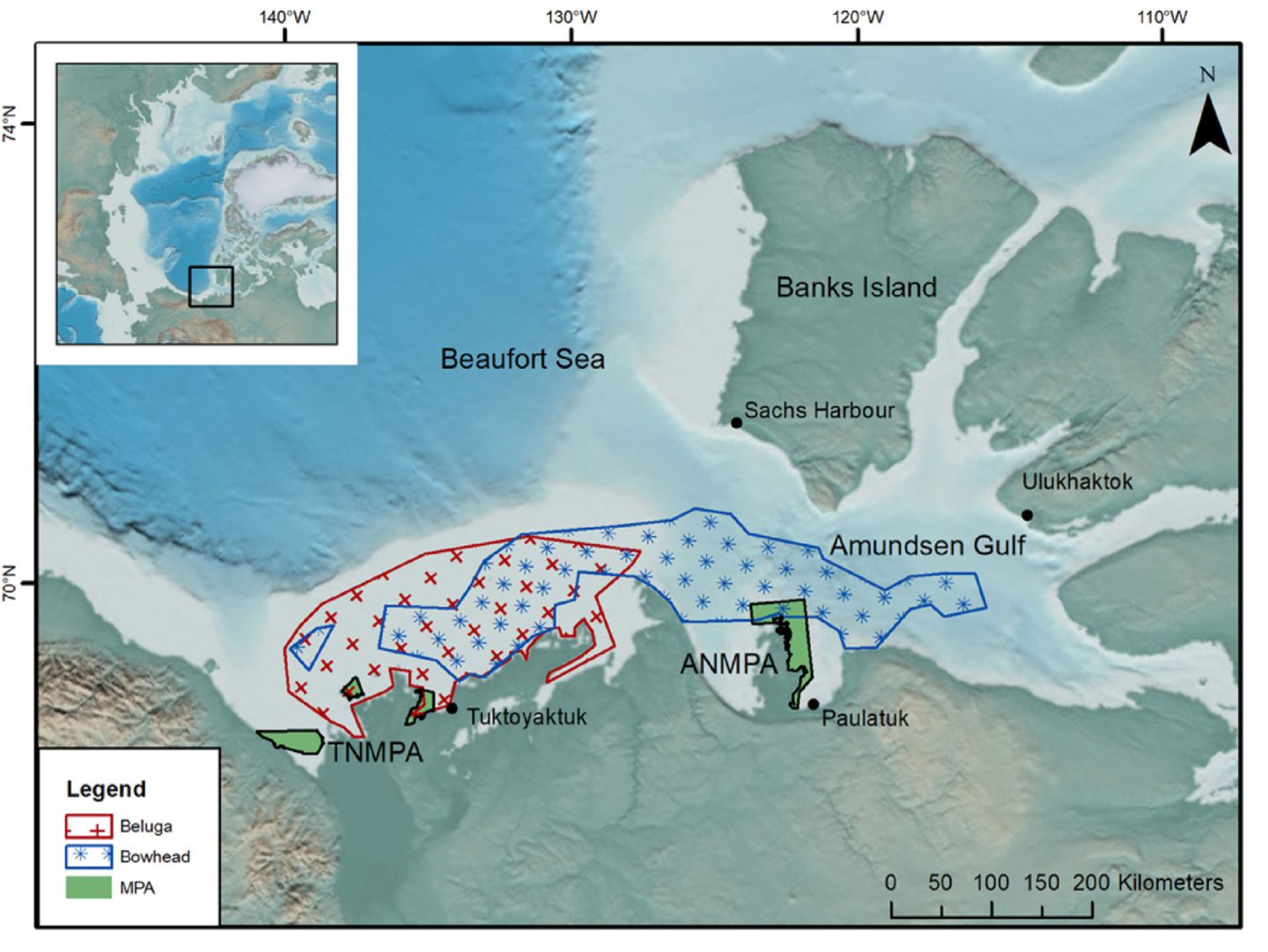

Bowhead whales, a close relative of the North Atlantic right whale, and beluga whales are the two species most likely to be affected by an increase in ship traffic through the Amundsen Gulf in the eastern Beaufort Sea, which is also the western entrance to the Northwest Passage. WCS Canada has been listening to both ships and whales in this area using underwater recorders and we are growing concerned about the potential for conflict.

Researchers participating in a MEOPAR (Marine Environmental Observation, Prediction and Response network, a Canadian National Centre of Excellence) project, including scientists from WCS Canada, the University of Victoria, and Dalhousie University, recently published a paper looking at the common tools used for reducing the impacts of vessels on whales and how these might be applied in the eastern Beaufort.

There are two recently established Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the study area: The Tarium Niryutait MPA was established in 2010 specifically to help beluga whales, while the Anguniaqvia Niqiqyuam MPA serves a variety of species, from Arctic cod and belugas to polar bears.

But among the limitations of these reserves is that they cover a relatively small area and are not designed to meet the year-round needs of migratory species such as bowheads and belugas. Enforcing vessel travel restrictions in these remote reserves could also be difficult in a region with little infrastructure and few people.

There is also the question of sound, which does not stop at reserve boundaries. Sound is an important issue because in Arctic winter darkness, deep waters or under sea ice, it is a vital survival tool for mammals that need to stay in touch with their group, detect and warn others of danger, keep track of their young or locate food.

Sound travels more efficiently in water than it does in air, and some marine mammals can be heard across astounding distances underwater. But just as it can be hard to hear what someone is saying at a noisy party, whales face similar problems when their environment gets noisier thanks to human activities and vessel traffic. Scientists with WCS Canada have found that ship noise can be heard as far as 100 kilometres away, and sounds can be loud enough to affect whales even when ships are as much as 50 kilometres away.

This left the researchers looking at lowering vessel speeds, which has been shown to be a good measure for reducing accidental strikes and noise. Similarly, re-routing vessels away from sensitive areas could also help. Vessels travelling through the Arctic tend to move more slowly in any case simply because of the hazards these ice-dotted waters present, but the research team felt vessel speed was still a measure worth considering.

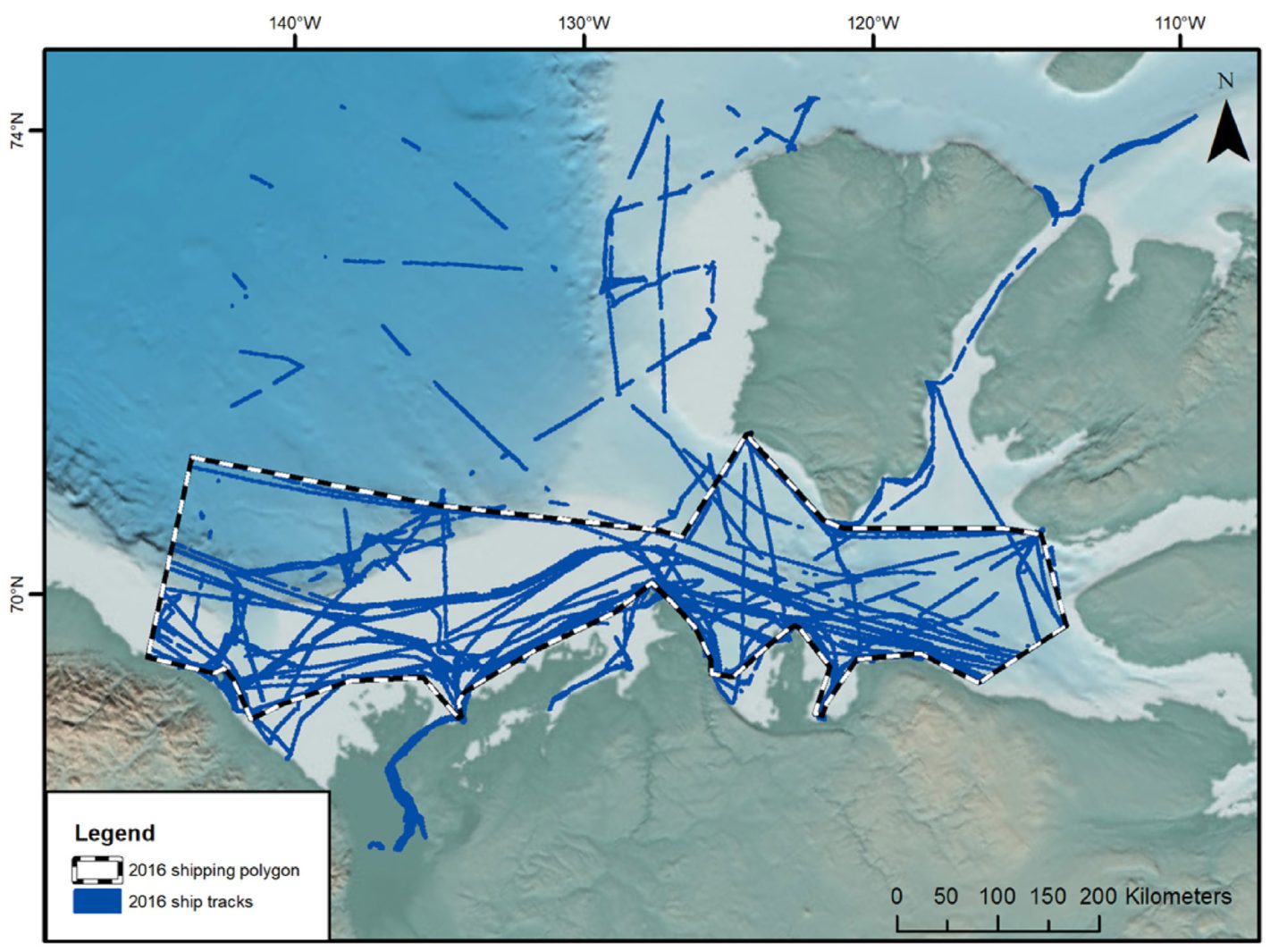

In order to better understand the impact speed or distance limits would have on vessels, the study tracked the movements of vessels through the area in 2012 through 2016 using satellite data from vessel transponders. The research team chose three vessels to represent different types of marine traffic: the Crystal Serenity, a tourist cruise ship, the Kelly Ovayuak, a tug boat that serves local communities, and the Nordic Orion, a bulk carrier. The results showed significant overlap, especially for the Kelly Ovayuak and the Crystal Serenity (the Nordic Orion stayed further away from the coast) with one of the MPAs.

The team then asked themselves, what would happen if these vessels were required to respect a buffer around the MPAs and/or were required to reduce speed when within a set distance of the MPAs (i.e., 100 kilometres)? The calculations showed that such restrictions would have only a modest impact on vessel operations, while lowering the risks to whales in and around the MPAs.

Using the average speed of the vessels, the study found that making vessels travel at 10 knots within a 100-kilometre area around the MPAs would add 2.3 hours to the Crystal Serenity’s original 55.6-hour voyage through the study area, and 2.6 hours to the Nordic Orion’s original 40.2-hour journey. It’s possible the cost of these additional hours might be partly offset by fuel savings gained by travelling at slower speeds.

The study also considered if vessels should be required to have local observers onboard to watch for whales. This could be an effective measure for avoiding collisions with whales and would create a new source of local employment. Again, there would be logistical challenges, but possibly lower than for certified ship pilots, a scarce commodity in the Arctic.

Overall, the study concluded that no one measure on its own is going to be a magic bullet. What is needed is a mix of measures and monitoring of effectiveness in order to develop effective combined approaches.

In fact, one of the biggest challenges—and opportunities—is to see the voyage planning stipulations in the international Polar Code for Arctic shipping fully implemented. That’s why now is the perfect time to start working with vessel owners to adopt these ideas on a voluntary basis and test their effectiveness. By proving that whales and vessels can co-exist under the right set of rules, we can avoid the kind of crisis that has developed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and help ensure better outcomes for species already struggling with a rapidly changing environment.

The Arctic has long been one of the quietest places on Earth, thanks to a modest human presence and a thick covering of sound-dampening ice, and species have adapted accordingly. But climate change is rapidly reshaping the Arctic environment, both physically and acoustically. That’s why we need to start planning now for a future where the sight—and sound—of a cruise ship or bulk carrier furrowing through Arctic waters is not a once-a-year occurrence, but a regular event.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

People & Culture

In this essay, noted geologist and geophysicist Fred Roots explores the significance of the symbolic point at the top of the world. He submitted it to Canadian Geographic just before his death in October 2016 at age 93.

Environment

The uncertainty and change that's currently disrupting the region dominated the annual meeting's agenda

Science & Tech

The Canadian High Arctic Research Station is set to open in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, later this year. How will it affect our understanding and appreciation of the North and the rapid change occurring there?