People & Culture

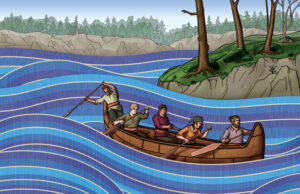

Rivers of resistance: A history of the Métis Nation of Ontario

“We were tired of hiding behind trees.” The ebb and flow of Métis history as it has unfolded on Ontario’s shores

- 4405 words

- 18 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Places

Once a notorious sulphur emitter, Sudbury is becoming a world leader in ecological restoration research

Talk about redemption. In the 1960s, the nickel mines around Sudbury, Ont., made the region the world’s number one sulphur emitter. The “Nickel City” was home to 7,000 acid-ravaged lakes, and its 80,000 hectares of barren land drew embarrassing comparisons to the moon. Today, however, the city is emerging as a global leader in the science of ecological restoration and mining rehabilitation.

Sudbury’s Vale Living with Lakes Centre, which opened in August 2011, is the latest evidence of the city’s reformed reputation, with scientists at the centre studying how to reclaim freshwater systems damaged by mining activities.

John Gunn, director of the centre and Canada Research Chair in Stressed Aquatic systems at Laurentian University, is leading a five-year study to investigate what kind of vegetation acts as “herbal tea,” detoxifying acid- and metal-damaged waters downstream. The land, he says, governs the health of the lakes.

Gunn credits long-term monitoring and restoration programs with providing the grist for the innovative research projects the centre is currently conducting, including how to use bottom-dwelling macroinvertebrates to indicate water quality. A collaborative effort by Laurentian University scientists, government and mining companies, these programs have seen sulphur emissions reduced by more than 90 percent over the past 50 years and thousands of hectares of once-barren land be regreened.

The centre’s scientists are looking further afield as well, to a region that could represent their biggest challenge yet. More than 500 kilometres to the north of Sudbury are the Hudson Bay Lowlands, a 245,000-square-kilometre swath that comprises the world’s third largest wetland. It’s a globally significant carbon sequester, but new mineral finds are set to open the area up to development. This is especially true in a 5,120-square-kilometre patch inside the lowlands known as the Ring of Fire, where the recent discovery of chromite, a metal used in the production of stainless steel, is producing the biggest rush of mining claims Ontario has seen in a century. The transport infrastructure necessary to exploit the site already has Gunn and his team applying their knowledge for the purposes of protection, before the region is developed. “We want to prevent another Sudbury from happening,” says Gunn. “We must learn from our mistakes.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

“We were tired of hiding behind trees.” The ebb and flow of Métis history as it has unfolded on Ontario’s shores

Environment

One of the most complex challenges for nature conservation comes from a simple question: what must we save?

Wildlife

The turtles we keep as pets don’t belong in the wild

Wildlife

Algonquin wolves face an uncertain future primarily because they can be legally shot and trapped in many parts of Ontario