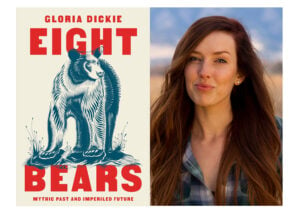

A polar bear, its paws covered in eider egg yolk, on Mitivik Island, Nunavut. Mitivik is home to Canada’s largest eider colony, but climate change has introduced a powerful threat: hungry polar bears. (Photo: Evan Richardson)

“If polar bear presence is a good proxy for patterns of nest depredation, then eiders should show a shift away from areas of high polar bear presence.”

According to Dey, it is still unclear whether predators, like polar bears, cause local eider population declines due to decreases in reproductive success or by causing female eiders to move elsewhere. Also, the average eider lifespan is 10 to 15 years, so it may take multiple generations to be able to accurately detect a change.

Changing ecosystems

Christina Semeniuk, part of Dey’s research team, says ecosystems like the Arctic are changing at such a rapid rate that it can be difficult for species to keep up.

“Being able to protect wildlife can be extremely challenging when these rapid rates of ecological change make it difficult to predict what’s going to be happening next,” says Semeniuk. “Who could have predicted bears would need to supplement their diets with seaduck eggs to such an extent in this part of the Arctic?”

Semeniuk says the outcome of the research was unexpected, since other studies have shown eiders to shift their breeding locations after a few failed breeding attempts.

“This just goes to underscore how working in anthropogenically altered environments can sometimes throw our predictions out the window.”

Click the video player below to watch a presentation by Patrick Jagielski, part of Dey’s research team and a University of Windsor student