Kids

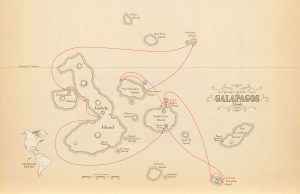

Giant floor maps put students on the map

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

- 1487 words

- 6 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

History

“In those days [the 1920s and 1930s], maps of the North were usually incomplete or inaccurate, so bush pilots made additions and corrections as they flew. When those crude efforts are compared with the excellent charts of today, we wonder why we did not get lost more often!”

Former bush pilot A.G. Sims wrote that in “Canadian Airmen on the map,” in the November 1975 issue of Canadian Geographical Journal [Read the story here]. Sims had flown during the post-First World War renaissance in Canadian aviation and aerial surveying, and his accounts of the characters, technologies, exploits and deadly disasters are fascinating and often first-hand.

And it’s a period that today’s Canadian Geographic readers will likely be familiar with. The October 2015 feature story “Drawn to Victory” details the same sudden injection of trained pilots and better and better planes, cameras and government support that caused the great blank spots on Canadian maps to shrink fast.

What Sims really highlights, though, is a specific type of permanent legacy left behind to honour this cohort of new explorers. Mixed in with familiar place names from the old ages of exploration (Hudson and Hearne bays, Mackenzie and Camsell rivers, Stefansson Island and so on) are several dozen that get their names from the pilots and surveyors, aircraft and crash sites that helped define the new era. The author himself had a lake in western Labrador named after him in 1953 — a rare exception to the government geographical names committee’s rule that new features could not be named after living persons.

Not surprisingly, then, a number of the pan-Canadian place names on the Canadian Geographical Journal’s list (included in the feature) commemorate stories with unfortunate endings. Fréchette River and Bellanca Lake, Que., on the mainland about 180 kilometres north of Anticosti Island, are named for pilot Clifford Fréchette and his Bellanca seaplane. Lost and out of fuel in the summer of 1939, he and his passenger starved to death attempting to “walk to the Gulf of St. Lawrence,” and it took searchers nine months to find their bodies.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Kids

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

Mapping

If you’ve ever had to help make a map, it gives you a whole new appreciation for the art form. As editor of Canadian Geographic, I’ve found myself more…

Mapping

Maps have long played a critical role in video games, whether as the main user interface, a reference guide, or both. As games become more sophisticated, so too does the cartography that underpins them.

Mapping

Canadian Geographic cartographer Chris Brackley continues his exploration of how the world is charting the COVID-19 pandemic, this time looking at how artistic choices inform our reactions to different maps