At camps, on the other hand, such winds have been known to blow tents down. Seasonal family domiciles the size of small houses, the main tent especially — where sleep our parents and, when it rains, where we eat — is sometimes as much as 10 yards long, six yards wide, and six feet high, virtually a tent that can accommodate a circus, if a small one. The men out minding the nets on any given day, it is generally just us children and the women there to tend to home fires. Which is what we’re doing when, out of nowhere, a wind appears and, like a starving animal, attacks our tent. Suddenly, the canvas dwelling is trembling to the point where we, its occupants, believe it is perfectly capable of being ripped from its moorings and flying to the barrens. Which is all Mom needs to leap into action.

Flinging aside the moccasin she is chewing to make it pointy, she jumps to her feet and grabs, at its middle, the central beam that serves as spine to the structure. An unpeeled spruce log propped up by two other spruce logs standing vertical at the tent’s front and back ends, this beam hovers just short of six feet above ground level. At five foot three and standing on tiptoe, Mom can barely reach it (and Rene and I are as yet too short to help her). At eight inches thick and 10 yards long, the beam has a weight that matches its bulk. For one small woman to withstand its might is one tall order; if it falls, the whole tent collapses, and Mom well knows it. Worse, if that beam falls on someone’s head, especially boys of four and seven, it kills them. To lose her sons to this bastard of a current of sub-Arctic flatulence? Out of the question.

The wind now grown to tornado proportions, it swoops and screams. And that beam shakes and trembles something terrible and the canvas material shakes and trembles something terrible and Balazee Highway shakes and trembles something terrible. Her arms held up above her head, her wiry frame vibrating like a string on a fiddle, she clutches that beam like no beam on Earth has ever been clutched before. And as she does, she shrieks at us, “wathaweek, wathaweek” (“get out, get out!”). Accordingly, Rene and I (and Itchy) go stumbling our way out the one door, our hands held over our heads as protection.

Once safely outside, we stand there buffeted and lashed and torn like scraps of paper, clinging to trees, to branches, to whatever object we can get our hands on, the roar infernal. All as we watch our tent engage in a dance that rivals in athletic virility the one danced by Satan and the archangel Michael on that dreadful day.

Fortunately, the stakes of willow that anchor its borders are sunk so deeply into the soil that they don’t budge.

We watch that structure shake and shake and shake and shake. Until, like a punctured balloon, it all comes down, tent, beam, and mother. And the whole structure lies there with the stove (unlit, thank God) and bed and grub box and, yes, Balazee Highway betraying their shapes like lumps in pudding, those shapes, for now, eerily inanimate. All that moves is the canvas of the tent, which flaps and ripples in a wind that will not stop. What now? Is Mom dead? Killed by the beam she has fought so bravely?

But no, there is movement. Like Sylvester the Cat (I will think later) crawling under a carpet to sneak up on lunch, the songbird Tweety, Mom’s cat-like form comes snaking and weaving its way through the crumple of flapping and rippling canvas until her head pops out the only door. Alive, unbowed, her hairdo a mess, she looks at us with an expression that says, “Cheest?” (“You see?”) “I told you I could do it.” Her eyes crossed slightly, she is seeing chickadees flying little circles around her head (she tells us later).

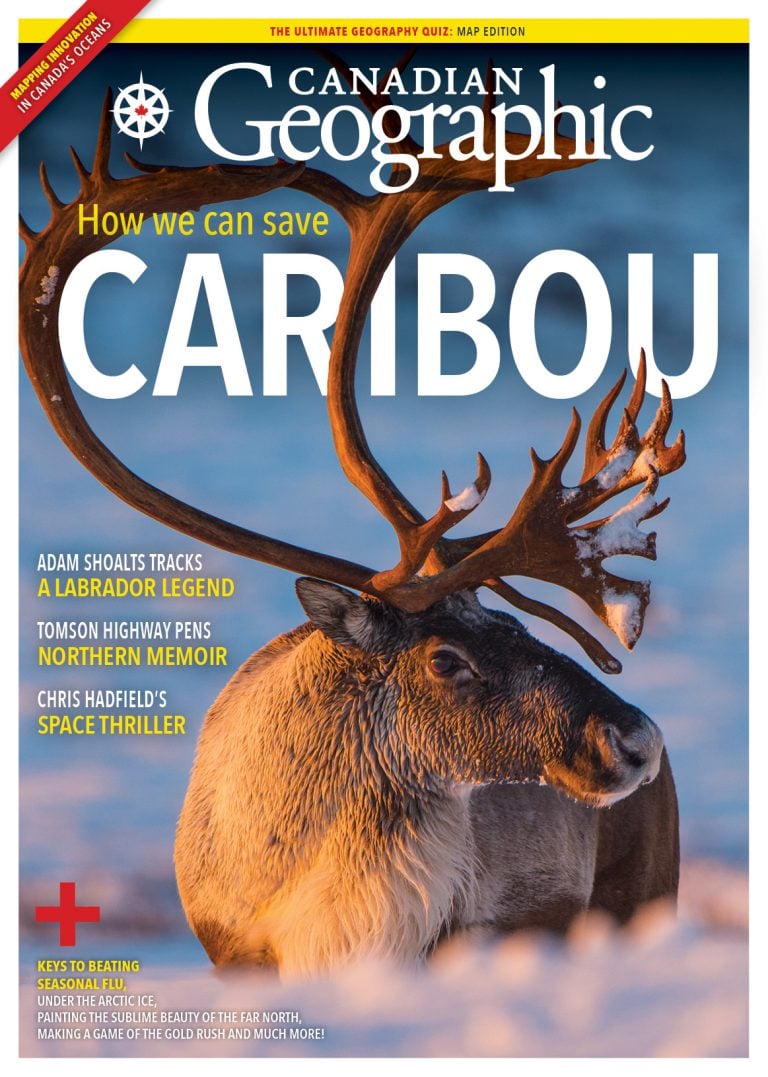

Excerpted from Permanent Astonishment by Tomson Highway. Copyright ©2021 Tomson Highway. Published by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.