Environment

Inside the fight to protect the Arctic’s “Water Heart”

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

- 1693 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

The director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation reflects on Indigenous progress in 2017 and looks ahead to 2067

In an opinion piece published by the CBC in December, 2016, Ry Moran wrote that he hoped Canada’s 150th year would mark a turning point in the country’s relationship with its Indigenous Peoples. As director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, Moran has a challenging mandate: ensure that both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada can access the often painful truth of our shared history, so that we can move forward in mutual respect and understanding. Here, as the sesquicentennial celebrations draw to a close and Canada looks ahead to its next 50 years, Moran reflects on the progress we’ve made — and how far we’ve yet to go.

There have been strong efforts made to include Indigenous voices in the conversation about our history this year. I went to the opening of the new Canadian History Hall at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, and Indigenous Peoples and perspectives are now much more prevalent. That exhibition also covers things such as the residential schools and the Sixties Scoop, which is really positive. But there was a lot of other stuff happening this year that was not fully reflective of the much longer history Indigenous Peoples have on this land, so I think we still need to look at 2017 as a starting point on this journey of reconciliation.

What we’re basically talking about when we talk about truth and reconciliation in the country is providing voice to groups of people, specifically Indigenous people, who have been marginalized. As we go through this process of reconciliation, we’re going to start hearing from people who we’ve never heard from before in this country, or at least only heard from in certain contexts or framed in certain ways. Change is inherently uncomfortable, but I think we as a country, we as Canadians, need to become much more comfortable with discomfort. We need to find a degree of peace hearing messages that perhaps we don’t want to hear, don’t understand. And we need to try to create the spaces within ourselves, within our society, within our organizations and institutions, within public discourse, for these uncomfortable truths to emerge.

We have to remember that what we’re trying to do in this reconciliation process is create safe places. Indigenous Peoples’ safety has been affected by this colonial experiment that we’ve called Canada, and we have to think about what those historical figures represent now that this truth is coming out. How does it feel when an Indigenous child walks into a school that’s named for Sir John A. MacDonald — somebody who oversaw the destruction of his or her ancestors’ culture, identity and livelihood, with the intent to basically eliminate Indigenous Peoples from this country? What does it mean when an Indigenous person sees people who fought hard for the elimination of Indigenous Peoples represented on the currency that we trade, and on public sites and monuments? It’s a sign of the process of maturation that we’re going through as a country that we’re able to have a much deeper conversation about these figures and decide whether these are the types of people that we actually want representing us.

For anyone who’s travelled through countries that share our common British origin, it’s interesting how many places and spaces in Canada recall or evoke really specifically British memories and realities. We have to remember that that is a very recent layer that has been imposed upon this land. It’s not like once upon a time people went around naming mountains and rivers after individuals; there were meaningful connections and descriptors of the land embedded within the names that helped to give shape and identity to where we live, and to our relationship to the land. We’ve got this kind of national narrative that people “discovered” this place, and we pretend for a second that all of these mountains and all of these lakes didn’t already have names, that the land was empty and devoid of people and devoid of connections, but the reality is there’s a much deeper, much older narrative.

Sadly, what we see in the construction of colonial states such as Canada is that Indigenous Peoples have been pushed to the side specifically to enable the extraction of natural resources and the conversion of natural life on this planet into capital, and our planet and our ecosystems have suffered greatly as a result. So the process of reconciliation is not just about learning to get along as human beings, but also about understanding that all forms of creation have rights on this planet. That idea is embedded throughout the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and we’ve also seen it expressed very clearly by Indigenous groups here in Canada. We cannot begin to understand ourselves as humans until we understand the fact that we’re in a relationship with all forms of life. We are neither above nor below, but part of a very dynamic web.

I hope that by then we’ll have seen a fundamental shift in the level of understanding of Indigenous Peoples and their histories and perspectives. I also hope that society will have really recognized the harmful effects of colonization and the traumas that have been wrought upon Indigenous Peoples, and that we will have taken serious steps to heal those traumas. For Indigenous Peoples themselves, I’m hopeful that we’ll have seen enough support and the right kind of support provided to communities, to nations and to individuals across the country so that healing work is really able to occur.

I hope that things such as the Indigenous Languages Act will have taken major steps towards preserving and protecting Indigenous languages. I hope to see a very robust National Council on Reconciliation that establishes some baseline data to determine whether the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada are closing. I hope to see the number of Indigenous children in care reduced dramatically. I hope to see the overrepresentation of Indigenous Peoples in correctional facilities reduced dramatically. And I hope to see the wealth and wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples increase to a level that is at least equivalent to that of Canadians right now.

But the overall context to all of this is are we actually going to have a sustainable environment? If we do not take serious, dramatic corrective actions now, we could be faced with very serious climate change challenges 50 years from now. So while it’s nice to think that Indigenous Peoples and Canadians may have a better relationship in certain regards, everything is kind of hollow if we continue to destroy the planet that supports us.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

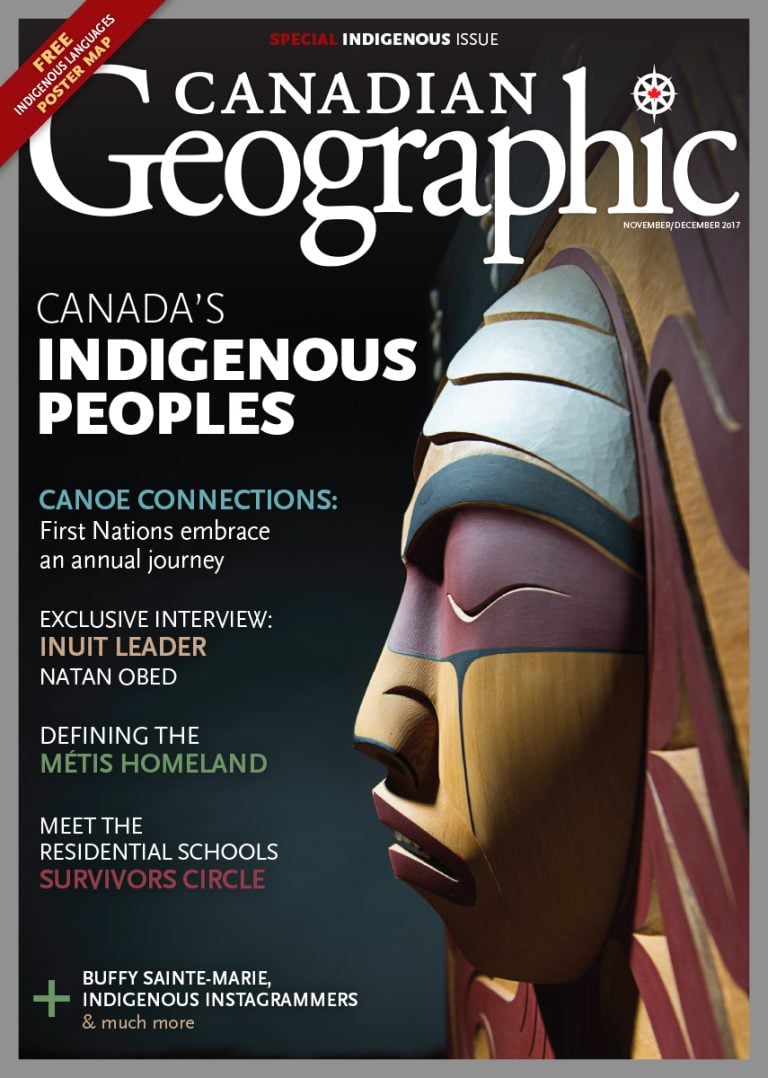

This story is from the November/December 2017 Issue

Environment

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

People & Culture

Indigenous knowledge allowed ecosystems to thrive for millennia — and now it’s finally being recognized as integral in solving the world’s biodiversity crisis. What part did it play in COP15?

Science & Tech

Celebrating Canadian Innovation Week 2023 by spotlighting the people and organizations designing a better future

History

A look back at the early years of the 350-year-old institution that once claimed a vast portion of the globe