Travel

Trans Canada Trail celebrates 30 years of connecting Canadians

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

- 1730 words

- 7 minutes

Travel

One writer’s journey to explore the life of Louis Riel

Saskatoon, my birthplace and current hometown, is an hour’s drive from Batoche, Sask., where Louis Riel made a last stand against colonization and racism with the Métis during the 1885 Resistance. My great-aunt’s mother was only eight years old as she watched soldiers ransack her Métis family’s farm holding in Batoche in 1885 (she lived to be well over 100). This is one of many lifelong connections to Riel that has always fascinated me, so I recently made a pilgrimage to Regina, where the Métis leader was executed by the Canadian government, en route to Winnipeg, formerly the Red River Settlement and Riel’s birthplace, where he began his series of stands against bigotry, colonialism and anglocentric governance.

In Regina, I make just one stop: the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Heritage Centre where, with special permission, I’m guided to the site of the gallows where Riel was hanged on Nov. 16, 1885, approximated by old photographs and documents, but unmarked in any official capacity. Nonetheless, it is still a gathering site for those who remember, particularly on the anniversary of his hanging. The museum itself has a small collection of artifacts including his prayer book and rosary, and the handcuffs used on him, which will be returned to the Métis Nation, likely the Saint-Boniface Museum that houses many of his mementos already. I lay down some tobacco and my beaded poppy at his hanging site, and snap a few photos.

When I arrive in Winnipeg, I check in at Inn at the Forks directly across the river from Saint Boniface and next to the new Canadian Museum for Human Rights. I meet Philippe Mailhot, my guide, expert on the many figures of the Red River Resistance and a wealth of living history, and we start a tour of the Métis neighbourhoods of Saint Boniface, St. Norbert and St. Vital.

Our first stop is Le Musée de Saint-Boniface Museum facing the Red River in the central neighbourhood of Saint Boniface. The museum is built out of the former Grey Nuns convent and school, which both Riel and his sister Sara attended and which now displays many of his artifacts, including locks of his hair, pieces of the rope that hung him, a game board he played while imprisoned, his shaving kit, and part of one of his coffins (he had more than one — his body was transported from Regina to Winnipeg in the winter and was moved around a fair bit before being buried at Saint Boniface Cathedral).

Around the corner from the museum is the Saint Boniface Cathedral, where Riel was buried along with many other luminaries of the Métis community, including Ambroise-Dydime Lépine, Riel’s second-in-command during the Red River Resistance. Mailhot and I admire the stained glass, varying styles of architecture and statues before roaming the grounds and paying our last respects in the cemetery. Offerings are regularly left at Riel’s resting place, from gifts to tobacco to sweetgrass.

Farther up the street is Université de Saint-Boniface, founded in 1818, making it the oldest post-secondary institution in Western Canada; Riel attended from 1854 to 1858. Today the grounds house a controversial statue of Riel, surrounded by his French and English quotes, while the statue itself depicts his vulnerability and torment. A few blocks away, the Lagimodière-Gaboury Park is located on the homestead of Riel’s grandparents, Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière and Marie-Anne Gaboury, where he was born. And near that is another park, the beautiful Parc Elzéar Goulet, commemorating Elzéar Goulet, the Métis leader who was violently killed in the subsequent Canadian military occupation of the Red River Settlement after Riel was exiled in 1872.

Heading south along the riverbank, Mailhot and I admire the Esplanade Riel footbridge. As we cross it, I see a sash design etched into the side of the bridge depicting a Creation story incorporating Indigenous and non-Indigenous teachings.

In St. Vital, south Saint Boniface along the Red River, we explore the Riel House National Historic Site, which is the site of Louis Riel’s mother’s home, and where his body was brought after his execution in 1885. The home has been preserved and maintained, and has programming throughout the summer, such as traditional activities and demonstrations.

From there we head to the intersection of Brady Road and Bison Drive (still under construction) known as Waverly West, which marks the spot where, on Oct. 11, 1869, Riel and his men stopped surveyors until land negotiations could be undertaken between the Métis and the Canadian government. From these backroads, you can still see the trees marking the remains of the Métis’ long river lots, despite over a century of development.

We then continue south along the river to St. Norbert to visit the site where the Métis barred the only road to the fort on the Pembina trail across the La Salle River, stopping Canadian government representatives from reaching Upper Fort Garry in late October of 1869. We then visit La Chapelle de Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Secours, an open air chapel built in gratitude to the resolution of the Red River Resistance, which resulted in the Manitoba Act, and gives credit to the divine help of the Virgin Mary in achieving the resistance relatively peacefully in 1869-70. Across the street is the St. Norbert Catholic Church and the Riel-Ritchot Monument, the former being the final resting place of Father Ritchot, who was key to negotiating with the Canadian government on behalf of the Métis, and where Riel and other Métis created le Comité national des Métis in early October 1869, the first national Métis government organization, leading to the creation of Manitoba.

The next day, I spend the morning at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights on the Winnipeg side of the Provencher Bridge. I take a Métis-specific tour of the building, beginning with a footprint thousands of years old discovered on the site during construction embedded on the main floor and ending with a spectacular view of the rivers and downtown Winnipeg from the top of the Peace Tower. Highlights of the tour include immense flower-beadwork panels commemorating destroyed and relocated historic Métis communities, such as Ste. Madeleine, the road allowance experience, and art installations by modern Métis artists Christi Belcourt and Sherry Farrell-Racette with highlights of Métis political organization and resistance.

After a delicious lunch of fresh pickerel in the museum dining room, I walk over to nearby Upper Fort Garry Heritage Provincial Park, the site where Thomas Scott was famously executed on Riel’s orders on March 4, 1870, and the home of his Provisional Government during the Red River Resistance. While the buildings are long gone, the gate has been reconstructed in its original place along with an LED display on the long west wall set to music and sound effects, highlighting some of the fort’s history, while flowerbeds outline the former sites of various buildings. From there, I head to the Manitoba Museum, which prominently displays Riel’s walking stick in the very first exhibit room. There are other Métis-themed exhibits including a log cabin, and my tour guide walks me through an exhibit-packed museum I remember from childhood visits.

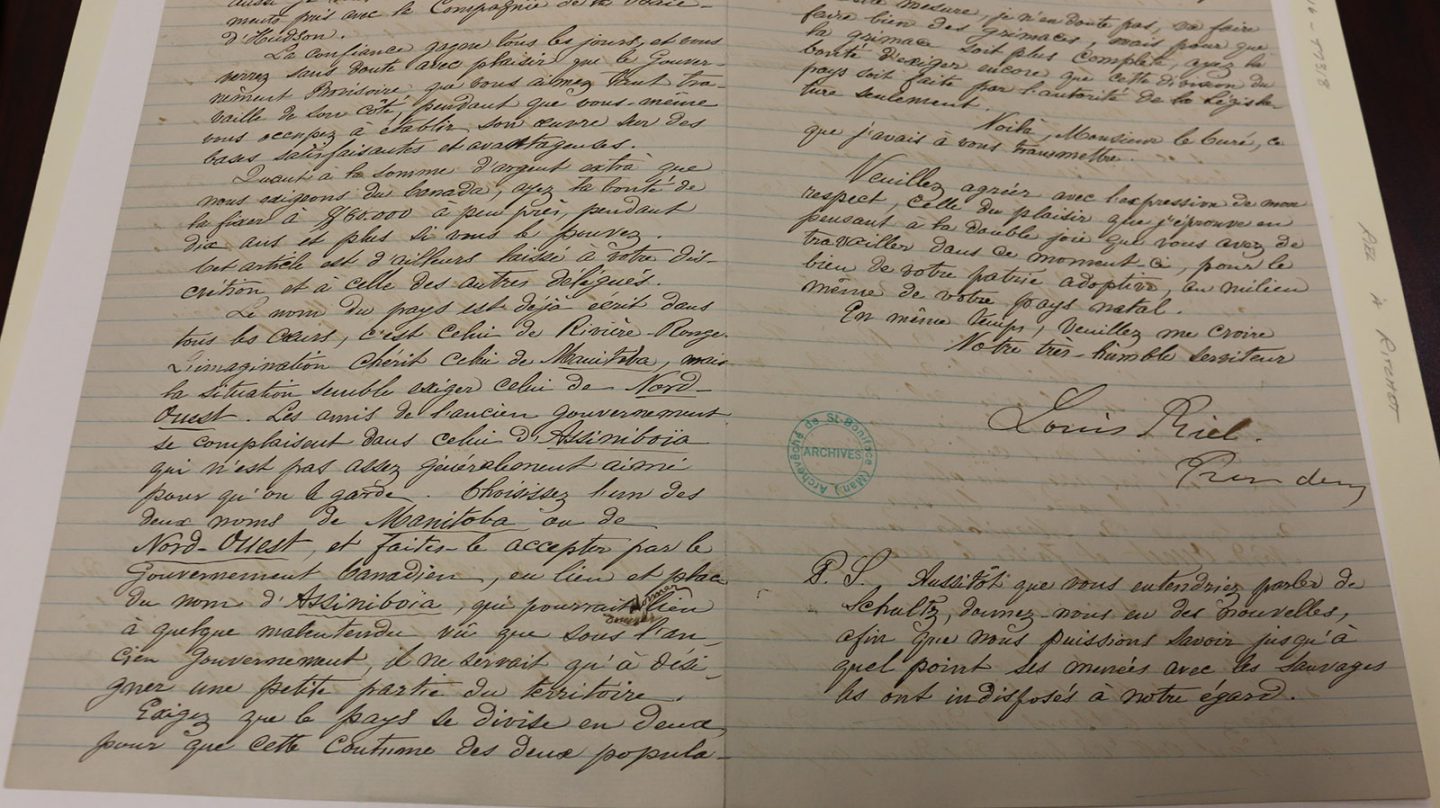

Early the next morning, I end my pilgrimage at the Manitoba and Saint Boniface archives. I photograph huge maps showing the original Métis homesteads along the Red River and delicately touch childhood mementos from the Riel family, while discussing history with a Manitoba Métis archivist. I read an original letter written by Riel. He suggests the name “Manitoba” for the province (a place name referencing Manitou, or the Great Spirit, in Nehiyaw [Cree] and Anishinaabe [Ojibwe]) among others. It is truly wondrous to touch a piece of history like this, and in Winnipeg, Riel’s history is everywhere.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

People & Culture

A celebration of the real Louis Riel, Métis leader and Manitoba founder, on the 150th anniversary of the Red River Resistance and the 175th of his birth

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

Travel

Inspired by age-old travelways, a new canoe route knits together the Trans Canada Trail