Travel

The spell of the Yukon

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

- 4210 words

- 17 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Exploration

Far beneath Alberta’s Castleguard Mountain, cave diver Martin Groves swims farther and farther into a pitch-black unexplored passageway. The beams of four powerful flashlights lashed to his helmet provide the only glimpse of his surroundings. After dropping for 19 metres, the flooded sump levels out, and Groves glides through a gently rising break between layers of limestone, a seam that’s two metres high and about 10 metres wide. Scalloped walls indicate that strong currents once surged here, but today, the water is still and clear. Groves’ fins kick up a fine dusting of sediment. The 39-year-old veteran caver from Wales methodically unspools white line from a reel, connecting it with strips of inner tube to rocks on the bottom of the sump. This line is helping him survey the new passage; it’s also a lifeline leading out.

On his chest, Groves wears a homemade rebreather, an advanced piece of diving gear that scrubs CO2 from exhaled air, then reinjects oxygen so that the gas can be inhaled again. Unlike scuba, or “open circuit,” equipment, where every breath is vented, a rebreather allows divers to remain underwater for an extraordinary length of time. (Groves’ lightweight system can operate for four hours; some bulkier units can last much longer.) Chemical reactions inside the rebreather warm the recycled air and, by extension, the diver — a significant advantage in Castleguard’s frigid waters.

After covering 845 metres in more than an hour underwater, Groves spots “the magical mirror image of air” above. His heart races, and moments later, he surfaces into a muddy, lake-filled chamber. He is through the sump.

The shoreline that Groves crawls onto has never seen human footprints before. His lights reveal a subway-like tunnel, at least three metres in diameter, disappearing into the darkness. Groves, normally a reserved man, a high school math teacher at home, can’t resist the urge to howl. A throaty echo reverberates back, indicating significant open passage.

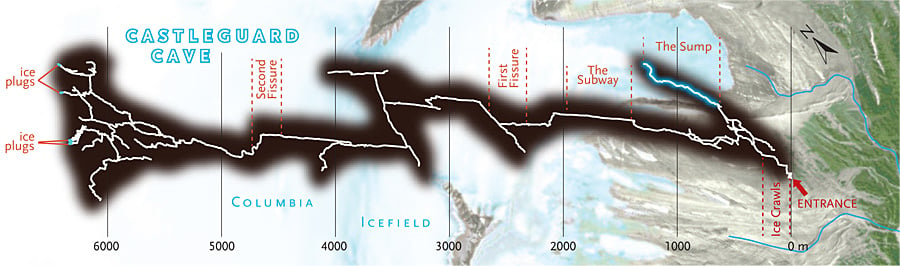

It’s April 2010, and this isn’t an ordinary cave that Groves is “pushing” (adding distance to). With 21 kilometres of surveyed passages, Castleguard is already Canada’s longest cave. Stretching under the Columbia Icefield in Jasper National Park, Castleguard is internationally renowned for its remote alpine location, its phreatic tubes (perfectly round passages) and its sapphire plugs of intruded glacial ice. Unlike most cave networks, which tend to spider out, Castleguard’s main trail extends in a relatively straight line, more or less parallel to the sump. A journey to its terminus is comparable, in challenge and commitment, to an ascent of El Capitan’s legendary Nose route, in California, says veteran caver Greg Horne, a resource management/public safety specialist with Parks Canada in Jasper. Even in systems such as Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, which has more than 620 kilometres of explored passages, an exit is never as far.

Groves begins to remove his dive kit, then pauses. Alone, beyond a flooded sump, in a remote cave, he might as well be on another planet. If he gets into trouble here, rescue is all but impossible.

During the 70-minute dive to reach this chamber, Groves’ right hand went numb, the result of a faulty dry glove, and one of his two oxygen meters was giving strange results. (Divers using rebreathers must vigilantly monitor oxygen levels to avoid toxicity.) Taking off his dry suit without help would not only be difficult but also risk damaging a zipper or gasket. A leak in this 4°C water could pose a serious, potentially fatal problem.

On the other hand, wonders Groves, when will he get this opportunity again? This is his third expedition to Castleguard, and getting here required massive support: seven British cavers and 20 members of the Alberta Speleological Society had dragged his heavy diving gear up the Saskatchewan Glacier in sleds, rappelled down the initial eight-metre drop into the cave, then crawled for a few hours through cramped, icy passages to reach the sump. An extensive cave network could continue beyond the sump, speculates Groves, and perhaps prove even longer than the known Castleguard system. The heart of caving lies in the discovery and exploration of new passageways — an addiction that’s luring him onward.

Then “a cold calculating logic took grip,” says Groves. “It’s critical to maintain a very defensive attitude when caving. Contrary to popular belief, this is not a sport for adrenaline junkies.” To safely explore and map the unknown system ahead, he’d need a partner.

Groves takes one last long look at the beckoning void, then pulls on his mask and sinks underwater. The unexplored cave settles into silence. But even as he fins back to his support team, Groves begins planning a return.

Very few opportunities for genuine exploration remain anywhere on the planet, and in Canada, alongside oceans, caves arguably represent the last great frontier. “We have vast areas of potential and very limited manpower,” says Chas Yonge, the operator of Canmore Caverns in Alberta’s Rockies and a seasoned member of Canada’s tight-knit caving community. “In Britain, it’s not uncommon to see a couple thousand cavers descend on a single region each weekend. Until recently, you’d be lucky to find 10 really active cavers in all of Alberta. Bit by bit, that’s starting to change.”

Four months after Groves’ dive added length to Castleguard, Canada’s deepest cave was dethroned by a new contender. The long-standing depth record — 536 metres, held by Arctomys Cave in Mount Robson Provincial Park, B.C. — was shattered by a find in southeastern British Columbia’s Flathead wilderness. These were just two breakthroughs in a series of significant discoveries that Yonge and others describe as the “dawn of a new golden age in Canadian caving.”

The journey down what is now Canada’s deepest cave began in 2002, when members of the Alberta Speleological Society spent the summer poking around the limestone deposits south of Fernie, B.C. Most leads yielded nothing. “It was frustrating,” recalls Gavin Elsley, a Welsh caver who had just moved to Canada at the time. “A lot of driving, a lot of hiking, and nothing to show for it.”

As frosts approached and the larch-peppered hillsides of the Flathead River valley turned yellow, cavers explored a recently discovered promising entrance on Mount Doupe, although they managed to penetrate only 100 metres before winter snows clogged the way. Still, they sensed they were onto something big. “The cave just kept huffing and puffing,” says Elsley. “Blowing out air in the morning, then sucking it back in each evening.” On a hot day, so much cold air blasted out the entrance that someone standing 20 metres away would get chilled. The cavers named their discovery Heavy Breather.

All caves breathe, but large drafts indicate one of two things: significant volume (changes in barometric pressure force air in and out) or a second entrance (cold air sinking out the bottom entrance or warm air venting from the top). As soon as the snow melted the next spring, club members began returning to Heavy Breather every weekend to survey and explore. By summer’s end, they had pushed the cave to an impressive depth of 350 metres.

It was the potential for something big that lured one Calgary caver back repeatedly in the winter of 2003-2004. Travelling by snowmobile to the remote region, Jason Morgan was often forced to dig out the entrance (a task that occasionally proved impossible). In 16 solo explorations, he pushed Heavy Breather to a depth of 500 metres — an epic effort that made it Canada’s second deepest cave. But then progress stalled; the cave appeared to have bottomed out.

Meanwhile, a nearby cave — 150 metres higher on the same mountainside — was showing promise. Discovered in 2003 and named Pachidream (because an elephant could fit in its immense entrance), the cave was quickly pushed to a depth of 330 metres. If the caves could somehow be joined and Pachidream’s additional 150 metres tacked on to Heavy Breather (see map on page 46), the new system would be the deepest in North America, outside Mexico.

Surveying new passageways is an integral part of caving’s well-established ethical code. “Scooping booty,” or racing ahead without meticulous note-taking, is frowned upon (see How to map a cave, above). The data collected are so accurate that during multi-year projects, such as the Heavy Breather/ Pachidream survey, each season’s results must be adjusted for changing magnetic declination (the angle between true north and magnetic north), otherwise looping passageways won’t line up. In this case, three-dimensional line plots showed that the two caves were aligned on the same tear fault. (Small tear faults run perpendicular to massive regional thrust faults in the southern Rockies and accommodate localized strain.) The race was on.

For the next five years, Alberta Speleological Society members poured immense time and effort into exploring leads and digging away at clogged passages. More than 35 cavers spent over 2,500 hours underground, rigging 110 vertical pitches with rope. Cavers refer to the methods and skills used to descend (and later ascend) these sheer drops as “single rope technique” (SRT). While closely related to the techniques of mountaineers and climbers, SRT uses equipment specifically designed to operate in chronically damp and muddy environments. The biggest continuous vertical drop in Heavy Breather — more than 50 metres, and named Well of Souls for the dripping water that produces a sound eerily reminiscent of voices — requires cavers to lower themselves down (or climb up) five consecutive lengths of rope, each anchored to the wall at the top and bottom with expansion bolts.

A breakthrough came when Elsley managed to pass a constriction in Heavy Breather known as the Naked Squeeze (it’s so tight, he had to strip and compress his ribs). Once beyond, he found a passageway “big and flat enough to drive a train down.” Named the Northern Line, it ended in a sandy pit. Roughly 15 metres beyond, according to survey data, lay Pachidream.

After enlarging the Naked Squeeze with blasting caps and hammers, cavers spent another two seasons exploring leads around the Northern Line: bolting climbs, draining pools, digging, making slow progress. Nothing went anywhere. Determined to track the draft that whistled through the passageways, a group of cavers brought smoke bombs down to the Northern Line in August 2010. Just as the first one was about to be ignited, someone spotted a tiny crack three metres above the sandy dig. Katie Graham, the smallest in the group, was hoisted up on shoulders and managed to cram her way in. Wriggling forward, she followed the tortuously twisting passage for 65 metres, until it ended in a blind drop. Peering over, she spotted the glimmer of reflective tape in the darkness below. It had been left behind by cavers in Pachidream years earlier on the off chance that a connection would come through the roof. Elsley, who had been following Graham, descended and confirmed that the caves were indeed linked — a combined depth of 653 metres.

Caving is very much a team effort, with each new discovery building on what came before and no one holding ownership of a project. So rather than rush onward, and because they needed more equipment, the cavers returned to the surface by the route they had come. That week, the call went out across North America, inviting everyone who had been involved in the exploration of the caves to join in the first “through trip” (in one entrance, out another) on Aug. 14, 2010, when Canadian caving history was made.

One of the most significant aspects of the eight-year effort is that it was driven by young, enthusiastic and mostly Canadian-born cavers. It represented, in the words of Yonge, “a passing of the torch.” After many years, a new generation was picking up where the first wave of caving enthusiasts — mostly British émigrés — had left off.

Caves have offered shelter to humans for millennia but speleology — the study and exploration of underground passages as a sporting and scientific endeavour — is a relatively new phenomenon. Frenchman Edouard-Alfred Martel, known as the “father of modern speleology,” pioneered the cross-disciplinary pursuit of all things cave- and karst-related in the late 1800s and early 1900s, combining chemistry, biology, geology, physics, meteorology and cartography. After the First World War, interest in “potholing” mushroomed throughout Britain and France, and it was from these hotbeds that the activity gradually spread, with enthusiasts turning their gaze abroad.

There had been sporadic interest in Canadian caves prior to 1965 — most notably, the early-20th-century explorations of Arctomys by A. O. Wheeler, Conrad Kain and other alpinists of the day — but it was the arrival of British professor Derek Ford at McMaster University, in Hamilton, Ont., and his formation of the Karst Research Group that changed the face of Canadian caving forever.

From 1965 to 1976, Ford’s students, many of them skilled British cavers, scoured limestone deposits across the country, in particular the southern Rockies, methodically seeking and documenting subterranean passages. The vast majority of the world’s caves have formed in carbonate rocks, such as limestone and dolomite, which are soluble in organic acid and weak carbonic acid, produced when rainwater and carbon dioxide combine. As water seeks the water table, it sinks into a network of cracks, which, over long periods of time, are steadily enlarged by both chemical dissolution and physical erosion, forming cave networks.

In short order, the Karst Group tripled the known length of British Columbia’s labyrinthine Nakimu cave system (near Rogers Pass) and pushed Arctomys to 536 metres, making what was already Canada’s deepest cave the deepest by a long shot. In Castleguard, where an eight-metre drop just inside the entrance had stymied all previous visitors, they mapped about 18 kilometres of new passage, easily establishing it as Canada’s longest cave. One summer in Castleguard, two cavers were trapped underground when afternoon meltwaters flooded the entrance. Luckily, the pair was rescued when the waters momentarily subsided, but to this day, all subsequent exploration has taken place in winter or early spring.

In 1969, near the Crowsnest Pass — an area on the southern Alberta/British Columbia border that would eventually yield the greatest concentration of subterranean passages anywhere in Canada — members of the Karst Group found the Andy Good Plateau, which became known as “the promised land.” On this small plot of barren alpine karst, riddled with fissures and sinks, eight enormous caves were uncovered, including Gargantua, which boasts the largest subterranean caverns in Canada, and Yorkshire Pot, a maze of passages, second only to Castleguard in length.

As the Karst Group scaled down its efforts in the mid-1970s, an inventory of the country’s known caves was produced. In Cave Exploration in Canada, one chapter, “End of an Era,” focuses on the Andy Good Plateau, suggesting that with the major discoveries now complete, the future of Crowsnest caving — and perhaps Canadian caving in general — would be largely a case of tying up loose ends.

Given the evolution of caving in Britain, the sentiment was understandable. In that heavily trodden and probed countryside, most new passage arises from “digging,” with a typical project lasting a decade and yielding no more than a few metres. A pub in Britain’s popular Mendip caving district has a long-standing offer: one keg of beer to the team of cavers that surveys the most passage each year. The minimum length is just 50 metres.

But Canada is different. “There is so much new stuff available, it’s possible for every single Canadian caving trip to be about pushing new passageway,” says Calgarian Ian McKenzie, former editor of The Canadian Caver Magazine and the organizer of Groves’ expeditions to Castleguard Cave. “It’s just a matter of looking for it.”

Consider Sentry Mountain, near Crowsnest Pass, which for 40 years has been crawled all over by cavers. Four years ago, Chas Yonge stumbled upon a cavernous mouth en route to an established cave. “It was so immense, it could be seen from space using Google Earth. Inside lay the second largest entrance pitch in Canada, a monstrous 140-metre chasm.”

It is safe to say we have no clear idea of the number of caves in Canada or even all their locations. (Clubs and governments are now attempting to collect and organize years of survey data, but the process is in its infancy.) And of all the known caves, only a small percentage have been exhaustively surveyed. On the hillsides around Heavy Breather, for instance, lie another couple dozen unpushed caves; with heavy rainfall, lots of limestone and the highest density of caves in the country, Vancouver Island is another hotbed of discovery. “We just don’t have enough people to keep up,” says Elsley.

Even a cursory glance at the caving community in Canada reveals the relative obscurity of the activity. Between British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec, there are fewer than 1,000 members registered in clubs, with no more than 100 regular participants. In contrast, the Canadian Ski Council estimates there are more than three million active alpine skiers in Canada. The Alpine Club of Canada — an activity that’s just as rigorous as caving — maintains a membership of nearly 10,000.

It is tempting to stereotype cavers as rugged, macho types, says McKenzie, but this is not the case: “There simply is no average caver. The most unlikely people become involved. The cavers I know represent a completely average cross-section of Canadiana; men, women, accountants, factory workers, unemployed, doctors, young, old, you name it.”

So why, then, does Canadian caving remain in the shadows? To begin, there is the reflexive fear or revulsion many feel at the thought of squeezing through damp, cold, dark spaces far underground. “Ironically, most people absolutely love their first visit to a cave,” says McKenzie, “but the vast majority never go again. For a small fraction, it becomes a defining passion, an activity that shapes the rest of their lives.”

Then there is the difficulty of access. Unlike caves in Britain, which are rarely far from a paved road, most of Canada’s caves require long drives down rough roads, followed by multi-hour scrambles into the alpine. There’s also the question of critical mass. In the U.K. and France, the caving community is vibrant and social, with nearly every major university hosting a club. In Canada, an introduction to caving usually arises by fluke — someone joins a friend of a friend on a weekend outing.

Finally, as Yonge says, “caving is the antithesis to the instant gratification upon which our modern age is built.” Exploration is a slow, methodical effort. “It simply takes time, which is something in short supply these days.”

Near the base of Mount Tupper, in Rogers Pass, a turquoise spring, or “resurgence” to cavers, quietly burbles from a hidden cave entrance. The Karst Group probed the area in 1966, finding that dye released into sinks near the top of Mount Tupper reached the sump — two kilometres away and almost 500 metres below — in 53 minutes. The phenomenally fast time, indicative of open, air-filled passageways, screamed of big-cave potential.

In 1972, Mike Boon, an indefatigable Karst Group member, returned to dive the spring, which had become known as Raspberry Rising. After diving 30 metres and wriggling through a narrow underwater squeeze, Boon emerged into a spacious cavern. But here the route ended, the way forward blocked by what he estimated to be a 50-metre waterfall bursting from a crack near the ceiling. Intrigued, Boon returned again, with a friend and a collapsible ladder, or “maypole,” but they were unable to find a way past the falls.

For 40 years, something about the cave niggled Boon. Now in his 70s and living in Calgary, he mentioned the potential to a local caver. If Boon was trying to bait a disciple, he couldn’t have picked better than young Nick Vieira.

Strong and scruffy, Vieira is intimidatingly silent, until he starts talking about caves, at which point he bubbles over like a shaken soda pop. A bumper sticker on the 31-yearold’s Jeep, which has been his home for two years, reads: “Yes, I did just crawl out from under a rock.” Vieira is one of Canada’s very rare “professional cavers,” although the fact that his clothes are held together with duct tape and dental floss speaks to the visibility of the sport. Even American Bill Stone — one of the world’s most accomplished cavers, someone who has spent decades organizing heavily sponsored expeditions in search of the world’s deepest cave (currently Krubera Cave in Georgia’s Western Caucasus, at 2,191 metres) — is far from famous. Still, Vieira manages to make ends meet by guiding cave tours and spends every possible moment underground (an astounding 224 days last year).

Boon first told Vieira about Raspberry Rising in 2007, but it would be another four years before Vieira felt he had the skills necessary to have a look. Just getting to the spring is a challenge. Intense summer flooding means that the cave must be accessed during winter, yet it lies on an active avalanche slope in Glacier National Park that’s regularly bombed by highway maintenance crews. In late 2011/early 2012, heavy precipitation and unstable snowpacks kept the backcountry around Rogers Pass closed almost permanently.

At last, on Jan. 27, the area opened, and Vieira hauled his diving equipment to the cave entrance. Four days later, he returned to dive the sump, getting his first glimpse of the subterranean waterfall beyond. He thought it might be possible to scamper up. (Vieira, it should be noted, is a highly skilled rock climber.) The next day, he managed to ascend the slick face, alone, placing eight concrete screws to protect the route while occasionally being buffeted by the full force of the water. The demanding climb would be a stout accomplishment in daylight. In the darkness beyond the sump, encumbered by a dry suit, it was staggering. Greg Horne offers this perspective: “The consequence of an accident deep in a cave versus one on an open mountainside might be viewed as equivalent to the consequence of an accident in your own backyard versus one on the far side of the moon.”

Weather continued to play havoc with access late last winter, allowing for only eight trips. Vieira made the most of these opportunities, diving the sump 32 times, shuttling 30 loads of gear and equipment through the sump and, with a small team, exploring and mapping 2,043 metres of new passageway. Cutting through blue-grey banded marble that is as polished as a kitchen counter, Raspberry Rising contains speleothems (formed when the carbonate dissolution process is reversed and calcite precipitates out) on a scale seen nowhere else in Canada; soda straws (hollow mineral tubes hanging from the roof) as long as hockey sticks; and flowstone curtains (wavy sheets of calcite) the size of bedsheets. Yonge, who has accompanied Vieira on several survey trips, says it may be Canada’s “most beautifully decorated cave.” Vieira believes that Raspberry Rising holds immense potential: “We’re only scratching the surface of what’s there.”

After two long years, Martin Groves returned to Castleguard Cave this past April, his eyes set on the tantalizing passageway beyond the flooded sump. But just as Groves and a team of four supporting British cavers were landing in Calgary, the first Alberta Speleological Society support team made a heartbreaking discovery. They had broken trail up the Saskatchewan Glacier, found the wellhidden Castleguard entrance and unlocked the Parks Canada gate only to realize, with a mix of horror and amazement, that the cave’s initial crawls were filled, right to the roof, with ice.

After a flurry of satellite phone calls, the expedition was called off. Twenty-six Canadian support cavers unpacked their bags and began the long wait for next spring, when they’ll try again. Groves and a few others plodded up the Columbia Icefield with chainsaws a couple of days later to see whether there was any way past the obstacle, but it proved impenetrable.

Rather than drag themselves home with their tails between their legs, the Brits decided to probe Karst Spring, a small resurgence located in Alberta’s Kananaskis Country, just south of Canmore, and suggested that I come along for a peek. After lashing heavy dive cylinders to their sleds, the men charged off on unfamiliar skis and snowshoes, and I had to race to keep up.

For more than 20 years, cavers have sought, without success, a significant cave in this part of Alberta. Although a few divers had probed Karst Spring, none had made it farther than a few metres. No wonder, I thought as we arrived. The sapphire waters, perched beneath a slab of limestone, are no larger than a backyard wading pool and don’t appear any deeper.

Still, Groves and his dive partner Gareth Davies somehow managed to worm their way down a small, murky hole near the back of the spring. Using a system of ropes and pulleys, with help from a crew of cavers on the surface, they systematically pried aside underwater boulders. Bit by bit, the divers squeezed deeper and farther.

Five days later, they had surveyed 100 metres of new underwater passage and reached a depth of 38 metres before the limits of their apparatus turned them back. “The way ahead looks clear, and a return is planned,” says Groves, adding in his understated way, “a very pleasing result.”

It is the allure of the unknown — the possibility of peering into passageways that no human has ever seen — that holds cavers so firmly in its grasp. Unlike mountaineering, where a climber can see the summit long before arriving there, a caver entering new terrain has no idea what’s coming next. “Entering unquestionably virgin passage is a powerful experience,” says Horne. “What lies ahead could occupy you for an hour or a lifetime. It’s the type of moment that sits you back on your heels, makes you take an extra deep breath and acknowledge, ‘Wow, this could be big.’”

With sinks 1,000 metres above and 15 kilometres away, Karst Spring could one day become Canada’s longest and deepest cave. Or it could peter out around the next corner. You simply never know.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

Exploration

2022 is the International Year of Caves and Karst. Here’s why you should care about the hidden worlds beneath our feet.

Exploration

Meet Limiting Factor, the submersible leading us to new depths of ocean exploration

People & Culture

Canadian-born filmmaker and deep-sea explorer James Cameron helped celebrate his lifelong friend and mentor Dr. Joe MacInnis with a day of events at Canada’s Centre for Geography and Exploration