“One of the main reasons I paint is because I think Nature’s so wonderful that I want to try to get my feeling down about that on canvas if possible. I feel that when I am doing my painting it is a form of worship.” — E. J. Hughes

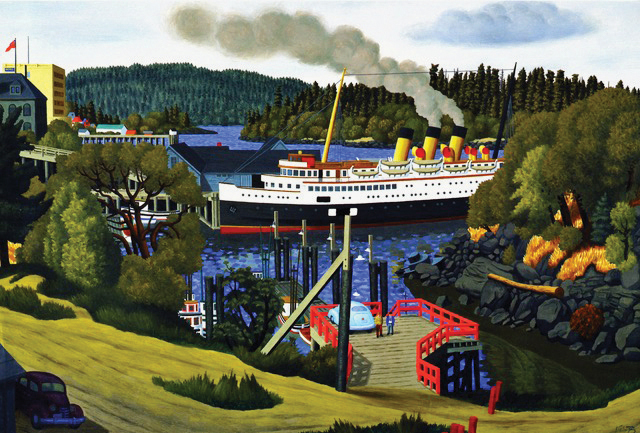

The paintings of Edward John (E.J.) Hughes (1913-2007) hang in the most important galleries of this country, and during his lifetime they sold for more than a million dollars at auction. Throughout his long career, when the art world seemed devoted to abstraction, Hughes painted local government wharfs, log-booming grounds and fishboats. These are images of Vancouver Island which ring true. When I travel up the island, I see the landscape the way he saw it.

Hughes just wanted to stay home, and he was able to dedicate his life to painting in undisturbed tranquility because of a remarkable contract with Max Stern, the owner of Montreal’s Dominion Gallery. One day in June of 1951, Stern sought out Hughes at his lakeside studio at Shawnigan Lake, north of Victoria. The art dealer liked what he saw, and bought everything the artist had on hand. And from that day until the Dominion Gallery closed in 2000, the gallery purchased everything Hughes painted—as soon as it was finished. Thus, this shy artist didn’t have to sell a painting, rarely gave an interview and never attended an “opening.”

Yet because of that Montreal connection, Hughes’ beautiful paintings are not widely known in the community where he lived and worked. Drawing on unprecendented access to the Hughes archive (which was assembled over many years by his helper, Pat Salmon) and with the participation of the Hughes Estate, my new book, entitled E. J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island, is designed to share his contributions. The paintings are accompanied by his notes and sketches, site photographs and images of the works in progress.

Born in 1913 in North Vancouver, Hughes grew up in Nanaimo, where his father worked “above ground” at the coal mine on Newcastle Island. In the artist’s teenage years, his family moved to Vancouver and, after enrolling in 1929, Hughes became the leading student at the new Vancouver School of Art. He graduated in 1933, at a time when the breadlines outside indicated that employment as an artist was futile, so he stayed on as a graduate student.

With his classmates Orville Fisher and Paul Goranson, Hughes endeavoured to make a living creating prints of Stanley Park, and painted murals in exchange for room and board, notably at Nanaimo’s Malaspina Hotel. In despair, he joined the army in 1939—just days before war was declared—and applied to become the first Canadian war artist, years before the program was made official. After training in Ottawa and Petawawa, he was posted to the south of England and then at Kiska in the Aleutian Islands. Hughes created more than 1,600 works during the Second World War, the largest single collection today housed at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

After demobilization, Hughes returned to Vancouver Island and, in 1947, was awarded the Emily Carr Scholarship by Lawren Harris. With this windfall, he spent the summer of 1948 travelling by bus up the island, sketching at Sooke and Sidney, then north to Ladysmith, Nanaimo, Gabriola Island, Qualicum Beach and Courtenay. These locations provided him with subject matter for the rest of his career.