Environment

Last bastion of ice

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

- 2894 words

- 12 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Travel

For most Canadians, driving on ice is a nightmare, but under the right circumstances, it can be an adventure — at least according to Northwest Territories tourism officials.

The territory is inviting visitors to take advantage of their last chance to drive the 187-kilometre ice road built annually on the Mackenzie River between Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk. Next winter, the historic highway will be closed as construction begins on a long-awaited permanent route on land.

In a post on their website, the NWT tourism authority describes the experience of driving on ice and snow through the unique geography of the Mackenzie delta as “dreamlike.” The surface is wider and smoother than that of a conventional road, there’s a good chance of seeing the aurora borealis in the clear, dark winter sky. Speed and vehicle weight limits are also strictly enforced to prevent holes from opening in the ice.

Photographer Richard Hartmier drove the famous ice road and documented his experience in the January/February 2016 issue of Canadian Geographic; his photos offer a glimpse at this unique aspect of life in Canada’s Arctic.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

Environment

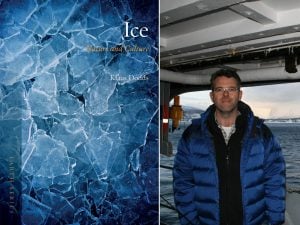

In his new book, Klaus Dodds delves into the fascinating natural and cultural history of ice

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

Exploration

A behind-the-scenes look at the adventures and discoveries of the passionate explorers funded by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society