Science & Tech

UN declares International Day of Women in Science

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

- 472 words

- 2 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

WHEN NALCOR, Newfoundland and Labrador’s provincial energy corporation, embarked on the Muskrat Falls project — an 824-megawatt hydro dam on Labrador’s Lower Churchill River — the company negotiated a deal with Labrador Innu to provide economic benefits and jobs.

The facility will ship power to Atlantic Canada and possibly New England through the Maritime Link, a transmission line being developed by Emera, the Halifaxbased energy conglomerate that owns Nova Scotia Power.

Under a profit-sharing agreement, members of the region’s Innu Nation will receive a five per cent dividend in perpetuity, while Innu businesses received $500 million in project contracts. According to Gilbert Bennett, Nalcor’s vice-president of energy for the Lower Churchill, the agreement included discussions about permitfree hunting, redress for earlier conflicts involving dams on the Upper Churchill River, and employment opportunities.

Of the project’s approximately 5,000 construction workers, more than 1,300 are from Labrador and 594 of those are aboriginal. About 600 people received education and training through the $30-million Labrador Aboriginal Training Partnership, and 400 got jobs at Muskrat. “You now have a workforce that has greater capacity than before,” he says, adding that many of the workers can get employment in other local natural resources projects.

While the Canadian hydro industry has started to forge a more collaborative relationship with First Nations, some initiatives still encounter conflict. Sarah Leo, president of the Nunatsiavut self-governing region, says residents of Lake Melville, downstream from Muskrat Falls, will face health risks associated with elevated mercury levels caused by the release of methane from decomposing plant matter submerged in newly flooded areas. Fish in such reservoirs, she says, contain higher methyl mercury levels and pose risks for residents who depend on them for food. Nalcor’s Gilbert Bennett says hydro developers have acknowledged the risk. “It showed up on day one of the environmental assessment.” The company has taken baseline readings and intends to monitor levels after the facility opens; it will issue contamination advisories if mercury readings in fish rise above certain thresholds.

In British Columbia, meanwhile, First Nations communities have taken to the courts in an attempt to block the $8.8-billion Site C project, a dam on the Peace River that will flood traditional fishing and hunting grounds subject to longstanding treaties. The project has been part of BC Hydro’s plans since the 1970s, and signatories to 1899’s Treaty 8 have always opposed it. “They’re going to destroy the last bit of the river bottom valley in northeast British Columbia,” says Roland Willson, chief of the West Moberly First Nation, adding that the dam threatens caribou, grizzly, elk and moose populations.

The conflict came to a head in July 2015 after the provincial government issued construction permits. Two First Nations sued, arguing the project violated 1899 treaty rights. According to court documents, BC Hydro and the First Nations communities couldn’t hammer out a consensus. While the Supreme Court of British Columbia rejected the First Nations petition last September, the Treaty 8 chiefs have continued to fight, enlisting support from other aboriginal groups and Amnesty International. Chief Willson points out that the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that Canadian governments can’t just go through the motions when they consult First Nations on such projects. But the government has stuck to its plans, and says that Site C will create economic activity for aboriginal communities. “There are going to be significant opportunities for local, regional and aboriginal businesses and workers in the region,” Bill Bennett, B.C.’s minister of energy and mines, said in a recent statement.

Other regions have used more than the promise of economic spin-offs, including profit-sharing and co-management, to avoid impasses. In 2009, Ontario Power Generation, the province’s electricity utility, and the Lac Seul First Nation, a community of 2,700 people that, in the 1930s, saw hundreds of families displaced by a hydro development, struck a historic agreement for the construction of a new run-of-the-river 12-megawatt hydro project at White Pine Narrows, also known as Obishikokaang Waasiganikewigamig. For the first time, Ontario Power Generation entered into joint ownership with Lac Seul.

In Quebec, the utility worked closely with the Cree on the $5-billion, 918-megawatt Eastmain 1-A-Sarcelle Rupert project in the James Bay watershed that involved diverting 70 per cent of the Rupert River’s flow toward new and old powerhouses, while minimizing flooding, avoiding ecologically sensitive habitats and protecting culturally significant lands. “The Cree were instrumental in designing the river,” says Richard Cacchione, president of Hydro-Québec production.

In Manitoba, two new projects — the 200-megawatt Wuskwatim, which was completed in 2012, and the 695-megawatt Keeyask, which is due to go into service in 2019, include formal partnerships with local First Nations, whose members own a 30 per cent stake in each. “I don’t think the social licence would be provided without a partnership agreement,” says Lorne Midford, Manitoba Hydro’s vice-president of generation operations and chair of the boards of the two corporations that run the shared generating stations. “There were wrongs done in the past, and we recognize that.”

The aboriginal communities have also played a significant role in determining the environmental impact of these projects, providing ongoing monitoring of fish and plant life near the dams. With one project, Manitoba Hydro agreed to reduce the elevation of the dam’s reservoir to address residents’ concerns about the extent of the reservoir lake. Says Midford: “We’re integrating the traditional knowledge in the environmental monitoring.”

WHEN CANADIANS flick on the lights, there’s a 63 per cent chance their electricity comes from hydro power. It is the largest electricity source in the country, and it’s no surprise that it is also a major contributor to the Canadian economy. These figures from the Canadian Hydropower Association illustrate hydro power’s economic impact.

355

Number of terawatt hours of electricity per year produced by Canadian hydro power.

76,000

Number of megawatts of installed capacity.

$37 BILLION

Amount the hydroelectric sector contributed to Canada’s GDP in 2013.

135,000

Number of jobs, including direct, indirect and induced, supported by the hydroelectric sector in 2013.

1%

Amount of overall U.S. electricity supplied by Canadian hydro power.

$10.1 BILLION Amount invested in hydroelectricity infrastructure in 2013.

$5.4 BILLION

Amount invested in 2013 by the industry to produce, transmit and distribute hydroelectricity.

$26 BILLION Revenue generated in 2013 from the production, transmission and distribution of hydro power.

$1.3 BILLION

The amount in federal, provincial and municipal tax paid by the hydroelectric sector (direct and indirect) in 2013 from the production, transmission and distribution of electricity.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the June 2016 Issue

Science & Tech

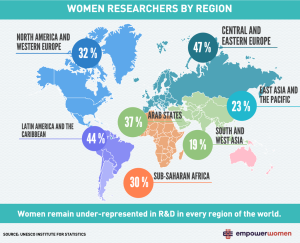

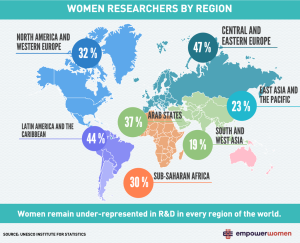

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

Science & Tech

Chris Henderson is the author of Aboriginal Power and president of Lumos Energy Clean Energy Value Advisors Inc. He advises indigenous communities across the country on…

Science & Tech

As geotracking technology on our smartphones becomes ever more sophisticated, we’re just beginning to grasps its capabilities (and possible pitfalls)

Environment

Carbon capture is big business, but its challenges fly in the face of the need to lower emissions. Can we square the circle on this technological Wild West?